‘Boxing The Past’

“You cannot establish your state [nation] without your past” states Youssef Fulgensio Onyalla, the Assistant Director for Archives at the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Sport, as he narrates the history of the National Archives of South Sudan. A sentiment that carries multiple, sometimes contrasting interpretations. We meet him in an indistinct residential building in Juba’s Munuki neighbourhood that temporarily houses the archives. The two floors of the house are stacked with carton boxes, organized along geographical and thematic categories, containing the tens of thousands of files that make up the South Sudan archive. The national archives have found a relatively secure, but temporary refuge here after decades ‘in hiding’ and years in a tent.

Youssef Onyalla, Assistant Director of the South Sudan National Archives.

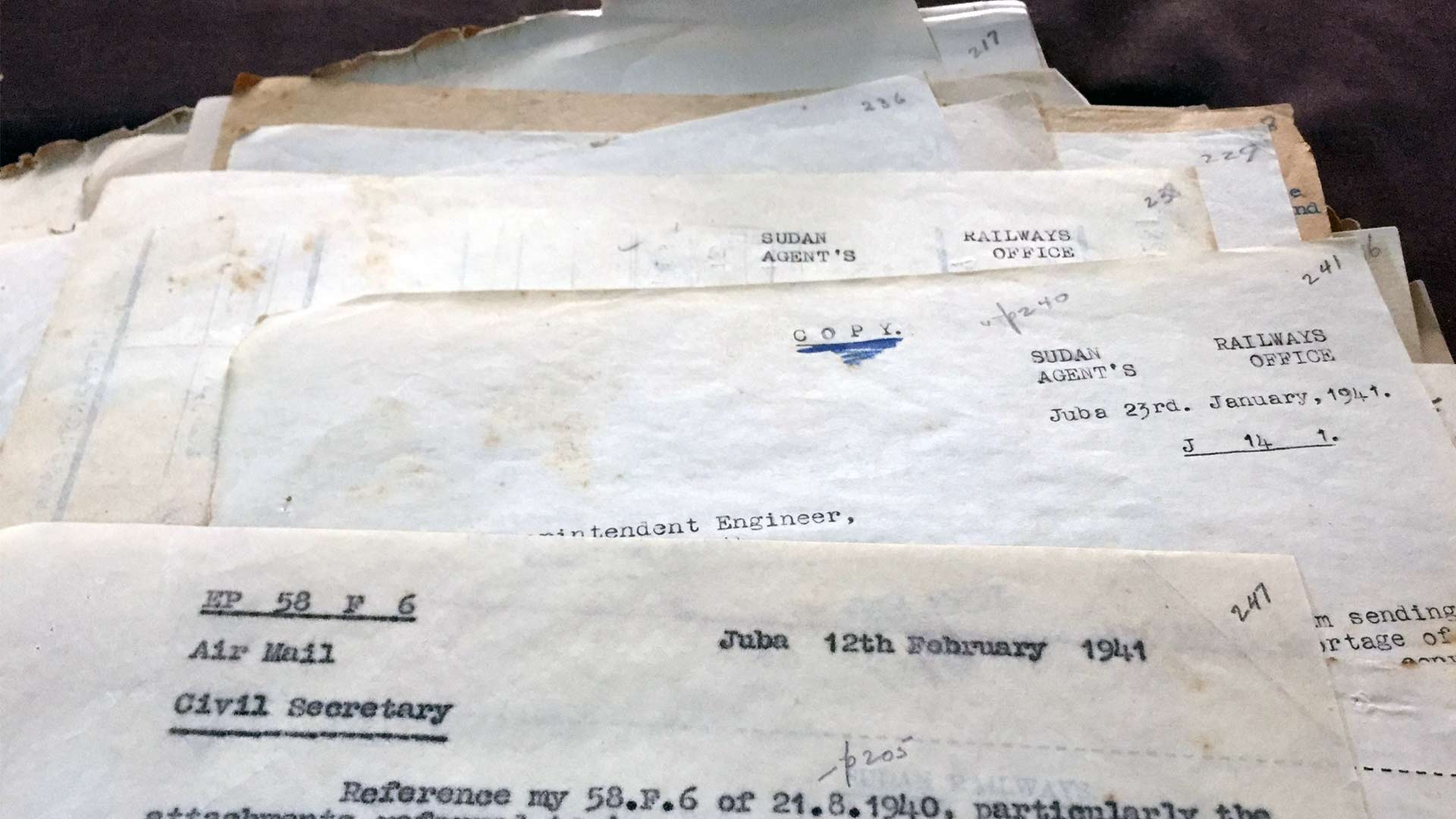

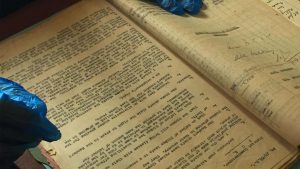

The national archives cover almost a century of foreign and domestic rule as the oldest documents in the archive date from 1899, the beginning of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium rule. The complete archives cover the epochs of British colonial administration and post-1956 independence governance. The very exercise of archiving the past is ambiguous as the Anglo-Egyptian colonial administration actively portrayed the region that is now known as South Sudan as history-less. Centuries on end were considered “dark” because of the absence of written records and it was claimed that the southern region possessed “no history before 1821 AD”.1 Harold MacMichael, who held senior positions in the service of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium for nearly thirty years, believed that the history of “early kingdoms and tribal movements in central Africa” could be ‘known’ only in chronological relation to the history of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and he divided the colonial Sudan in three areas and installed a hierarchy of historicity: southern Sudan suffers in oblivion and lacks “records”; “clues” for the east and west exist, but only in the “sphere of probability, likelihood and possibility”; and the north lives surrounded by direct evidence (both monuments and records) that has “survived” (in reference to material heritage).2 A similar division can be found in the chronicles of a young Winston Churchill, who divided the Sudan in the northern part that according to him is rich in history and “familiar to distant and enlightened peoples (…) drawn by skilful pen and pencil” and the southern part that knows only “a confused legend of strife and misery”.3

The portrayal of the southern region as history-less served to legitimize colonialism and ignored the existence of oral traditions. The various ethnic groups in South Sudan share and compose songs and stories of genealogical kinship and communal virtues that narrate histories of migration and speak of times before the arrival of Turco-Egyptian forces in 1821. These cultural resources do not only create a relationship to an ancient origin, but are continuously altered and renewed to reflect the present dynamics in which the stories and songs are performed. However, it is the colonial archive that South Sudanese politicians have turned to in defense of, for example, the contemporary boundaries of the South Sudanese nation state.

The colonial government kept a meticulous record of their governance of the ‘southern region’ and administrative communication between district and province levels, and these records were inherited by the Sudanese government upon independence in 1956. This raises the question as to whom did the colonial government hand over these documents to after independence? Nicky Kindersley, who worked as a coordinator for the Rift Valley Institute archives project, explains that in the period of Sudanisation, documents were transferred from British officials to their, mainly northern, Sudanese counterparts, some of whom were already involved in the administration under colonial rule. Up until the establishment of the national archives, the documents ‘lived’ a rather static existence and were kept in the offices where they originated – a practice that continues today as various ministries have extensive archives of their operation.

Mading Deng Garang, a former Minister of Culture initiated the establishment of an archive in the southern region during the Addis Ababa Agreement and established the Southern Regional Record Office in 1972. This office was unsuccessful in gathering and synthesizing the various provincial archives and it is only five years later, in 1977, when the Department of Archives was established under Lawrence Modi Tombe, the then-Minister of Culture that the national archives gained actual shape. The department was assisted by Dr. Douglas Johnson, a renowned historian of Sudan, to collect documents from the former colonial centres like Bor, Pibor, Fangak, Malakal, Kapoeta, Torit and Maridi. Majority of the documents are written in English and Arabic, but the archives also house court transcripts in the different colloquial languages, like Nuer and Lotuho.

The National Archives have been severely affected by the second war (1983-2005) and many documents got lost or were damaged as a result of inimical storage conditions. At the start of the second war in 1983, the staff of the archives of Central Equatoria State secretly and hastily moved files from the official archives to various locations in Juba to ensure these would not end up in the hands of the Sudanese army. Youssef Onyalla states: “They [the Sudanese government] wanted to destroy everything about South Sudan, its history, its identity”. For decades the archives found a scattered exile in the kitchen of the Juba Girls Secondary School and in the basement of the Office of the Governor of Central Equatoria State. Not only were existing documents affected by the second war, but also were no new documents added to the archives during the second war. Youssef speculates that there might be files concerning the southern region in Khartoum and requests have been put forward to the Sudanese government for return, but no documents have yet been exchanged.

The first public exhibition of the South Sudan National Archives (Juba, 2017).

In 2007, two years after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the archives were reassembled in a tent that offered very little protection against the elements and Nicki Kindersly jests that “termites have enjoyed a good portion of the South Sudan’s historical record”4. Since 2007, the archives department has embarked on the challenging task of emergency conservation and all attention has been directed towards safeguarding and digitizing existing documents. The national archives is awaiting transferal to its final destination, a former military officers’ mess currently under renovation opposite the mausoleum of John Garang. Until that happens the documents will remain stored in carton boxes in a house that was never intended to house the literal ‘memory’ of South Sudan.

Loes Lijnders

2 Ibid.,x.

3 Churchill, Winston S. 1902. The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan. London: Longmans, Green & Co., chapter one.4 Kindersly, Nicki. “South Sudan National Archives: New country, New Paperwork.” Published 14 March 2014 on The Imperial and Global History Network: http://imperialandglobal.exeter.ac.uk/2014/03/south-sudan-national-archives-new-country-new-paperwork/.

Munuki