To The Juba Wharf

Juba was established on a rocky ridge extending east from Jebel Körök (popularly called Jebel Kujur) to a bend in the Bahr al Jebel where it was deep enough for steamer traffic. Unlike many of South Sudan’s towns (Wau, Tonj, Shambe, Meshra-el-Rek, Rumbek, Bor, and so forth), Juba was not a former slaving station that had been remade into an outpost of military and civil administration. The site was chosen as a new administrative headquarters in 1927 by Arthur Wallace Skrine, the Governor of Mongalla Province and ‘a constant sufferer from malaria,’ after Gondokoro and Mongalla had each proved to be ‘unhealthy’ locations in his estimation.[1]J. N. Richardson, “Bari Notes,” Sudan Notes and Records 16, no. 2 (1933), 181-186. During a visit to the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.) station established by Archibald Shaw near a small Bari village, Skrine decided that the ridge running down to the river would be a healthy site for a provincial headquarters.[2]C.H. Piercy, 1966, Public Works in Equatoria Province 1928-1938 (SAD 298/4/2). Governor-General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1928, pp. 139-140. The village … Continue reading Building began in 1928 with a steamer office and the construction of a 22-mile road connecting the new station to the Rejaf-Aba road.[3]This road came to be known as the “Route Royale” after it was used by King Albert of the Belgians to make his way to the Congo to open the Albert National Park. The Juba Hotel was completed during the following year, in 1929, and government buildings and houses for officials were laid out along the ridge overlooking the swampy lowlands to the north.[4]Governor-General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1928, pp. 139-140. From this summit, where Ministry Road runs today, British officials could keep an eye on Burusoki, Juba’s old ‘Native Lodging Area,’ whose residents had been brought there to build the town.

By 1934, about one thousand people had settled at Burusoki, when, as a precaution against Yellow Fever, the landing ground was made into an anti-amaryl aerodrome: surrounded by a 3 km residential cordon and equipped with a medical officer and mosquito-proof quarters for medical inspections, isolation, and passengers. Residents were abruptly transferred to Burokorongo (today’s Malakia) and Burusoki was demolished.[5]Yellow Fever was detected in South Sudan in 1933. Officials considered moving the aerodrome, but no other suitable place could be found. To prevent the spread of Yellow Fever, a residential cordon of … Continue reading The new Native Lodging Area was laid out on a ridge rising from the bank of Khor-bou—which separated it from the hospital to the north and provided a stripe of scrubland where children could play—and then dipping into Khor Lobuyet to the south. It was composed of the Malakia Primary School and seven residential blocks, each of which were divided into ten plots demarcated by castor oil trees.

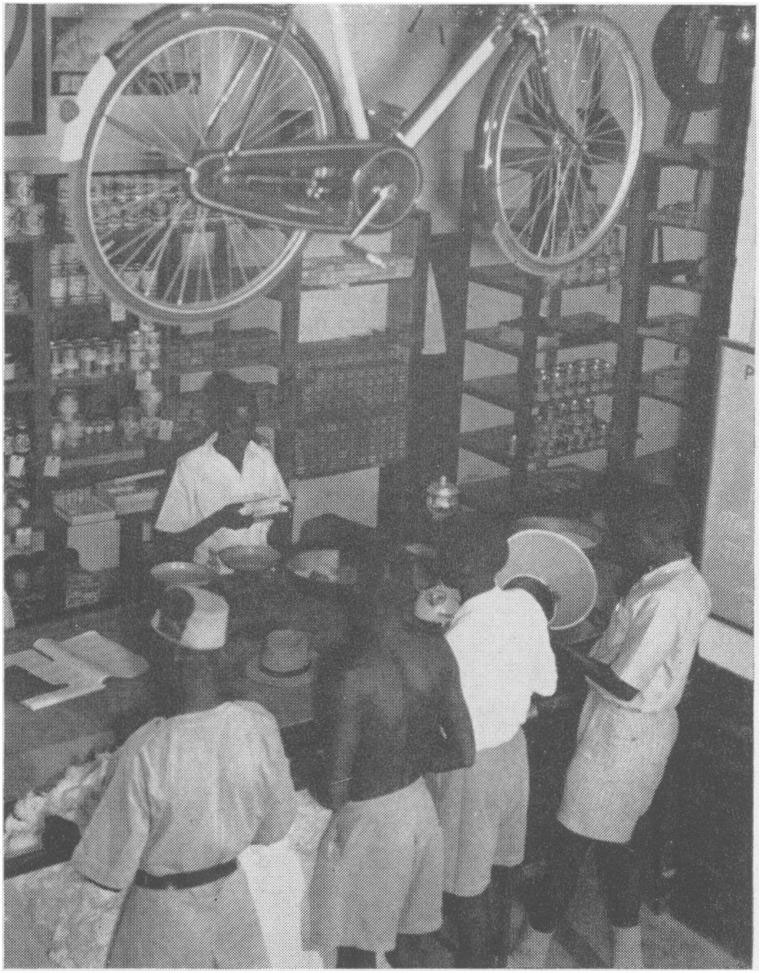

The province headquarters were moved to Juba from Mongalla in 1930.[6]Governor-General’s Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1930. p. 136. By the mid-1930s, travelers disembarking at the quay, where the White Nile steamer tied up, would have found themselves on a small wharf not far from the heart of a little colonial town of about twelve-hundred people. Directly in front of them lay a short stretch of road running parallel to the river. The well-stocked store of Mr. Crassus, a Greek merchant, stood at the crossroads, flanked by two shops with Indian proprietors and a row of small workshops and warehouses, a bakery, and several small cottages. About one kilometer to the west along the town’s principal thoroughfare one came to the Juba Hotel. Nearby, the town’s center was marked at a crossroad by a memorial stone which had been decorated with little plaques inscribed with the names of nineteenth-century missionaries, mercenaries, officers and administrators employed by the Ottoman-Egyptian regime (1820-1885): Louis Sabatier, Ferdinand Werne, Ignatius Knoblecher, Samuel Baker, Charles Gordon, Emin Pasha, Romolo Gessi, and Charles Chaillé-Long. The town’s main axis radiated outward from the stone. One road ran north to south, from the aerodrome, past the Juba Hotel and the Juba Hospital, across Khor-bou to Malakia, and then to Kator and the ferry-crossing. The other ran west to east, from the offices and residences of the town’s administrators (the district officer, doctor, nurse, public works and public health officials, and the agricultural officer), past the Mudeeria, the Hotel, and Mr. Crassus’ store, to the wharf where the White Nile ferry moored.

By 1935, if not earlier, the town’s population had begun to advance and recede throughout the year in a seasonal rhythm that was unmistakably linked to colonial labor demands. Between January and April, the town’s population grew with the arrival of petty traders, domestic workers and other casual laborers, family members and various guests and other visitors. Officials worried that this population growth would loosen customary bonds of authority and mutual aid and breed vice and idleness, diverting hands from agricultural work. So, each April, at the start of the rains, officers made their way through Juba, rounding people up, loading them into government lorries, and ‘despach[ing] them … to their home centres’ to begin farming.[7]L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), 7. During most years, the residents of Juba’s hinterlands could produce all their requirements, apart from trade articles; most people had little need for money, and no pressing reason to produce much more than they could use. Colonial officials imposed taxes across the countryside to ensure that on innumerable small and medium-sized plots, the farmers of Gumbo and other nearby settlements, produced a growing volume of ground-nuts, sesame, millet, and other foodstuffs, charcoal, timber and thatch for sale in markets in Juba.[8]J.N. Richardson remarked that two years after the town had been established, ‘the local population … still take little interest and have to be persuaded to supply the inhabitants with eggs and … Continue reading

The African Forces Line of Communication

Juba has always been a remarkably global city. Nowhere were the effects of these world-wrapping connections more visible than in the rapid expansion of the town in response to the Second World War. South Sudanese first felt the war because of Sudan’s border with Italian-occupied Libya and East Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Italian Somaliland). Italy entered the war in June 1940, and leaving nothing to chance, Anglo-Egyptian officials interned all Italian subjects in the country. By January 1941, the South’s Italian priests and nuns had been confined to the Palotaka Catholic Mission, an out of the way station where they would be unable to observe the movement of troops along the Juba-Nimule road. In Khartoum, cinemas contributed ticket sales to support the Red Cross.[9]Helen Foley, Letters to her Mother: War-time in the Sudan 1938-1945 (Castle Cary: Somerset, 1992), 40. One moon-lit evening in Atbara, an Italian aircraft dropped incendiary bombs and high explosives very nearly into the town’s ‘packed open-air cinema.’ (‘Miraculously, no-one was hurt.’[10]C.R. Williams, Wheels and Paddles in the Sudan (1923-1946) (Petland Press: Edinburgh, 1986), 100) And, in Juba, ‘trigger-happy police are said to have regarded most approaching planes as Italian, and succeeded in holing but not harming a Lockheed and a Gladiator!’[11]Anon., “The Growth of Juba,” Great Britain and the East (December, 1945), 42

Juba’s location, beside the major land and river routes leading north to Egypt, was a major reason why its residents felt the effects of the war so strongly. The start of the war turned the once sleepy colonial town—where lions were ‘met in the streets [and] buffalo canter over the aerodrome’—into a bustling entrepot of the Allied war effort.[12]Anon., “The Growth of Juba,” 42 ‘All the machines of war, planes, ships and lorries poured men and materials into Juba and bore them off to battle areas,’ wrote D.A. Penn, the Assistant District Commissioner in Juba.[13]Arthur Charles Beaton, Equatoria Province Handbook: Equatoria province (Khartoum, Sudan, 1951), 27. Between September 1940 and May 1941, war materials were moved from Mombasa to North Africa by way of Juba, requiring chiefs from Yambio to Kapoeta to raise 5,000 laborers to repair and maintain roads and reinforce bridges. Before the Second World War, about 2,000 tons of goods passed through Juba each year; by the early 1940s, about 60,000 tons per year passed through the town, an increase of almost 3,000 percent. So many planes overnighted in Juba in 1941 that the Juba Hotel was completely filled and the Sudan Railway’s Hotel and Hospitality division, which managed the hotel, had to use the corridors of the Juba Hospital to accommodate passengers and crews.[14]J.M. Pett & Geoffrey Pett, White Water Landings (Princelings: Norwich, 2016), 166. For comparison: during 1940 the Sudan Medical Service inspected and cleared of insects only 64 aircraft in Juba; … Continue reading

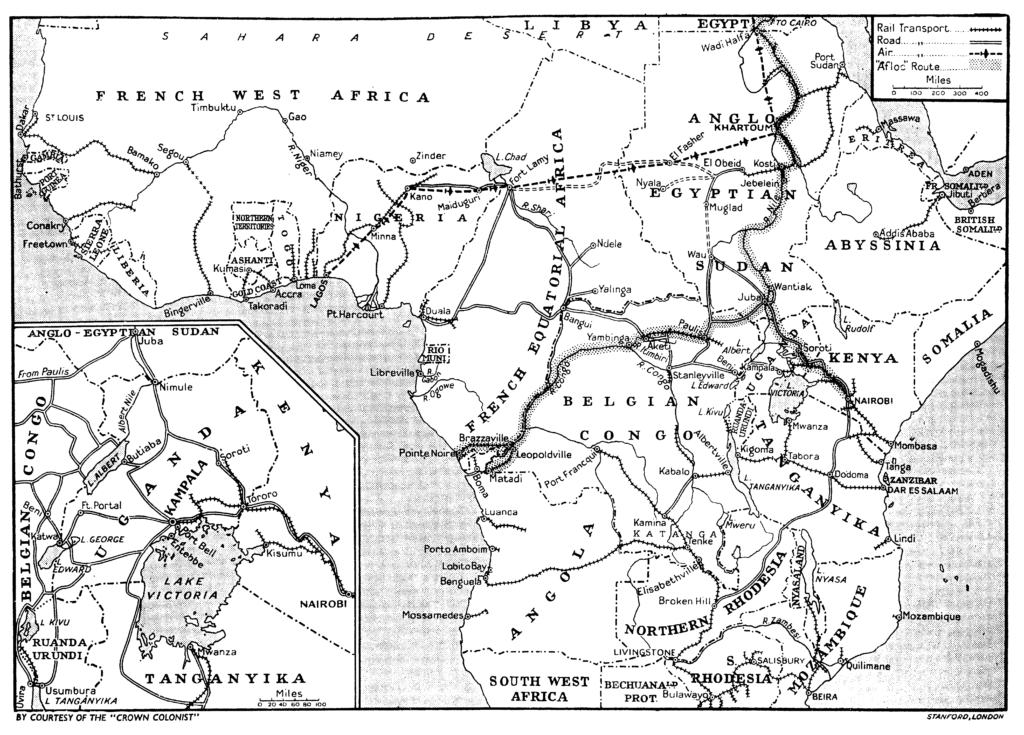

Every day, from the U.K., the U.S.A., and Canada, ships full of vehicles, tanks, petrol and coal, machinery, radios, explosives, weapons, ammunition, and equipment of every sort arrived eighty miles up the estuary of the Congo River. At the Port of Matadi (Belgian Congo) workers unloaded the ships and transferred the cargo onto trains, which carried it to Léopoldville (Brazzaville, today Kinshasa). At Léopoldville it was loaded onto barges and pulled by stern-wheelers to Aketi; it was then carried by rail to Paulis (Isiro) before being loaded on to trucks and carried by road to Juba. At Juba, all these ‘materials and machines of war’ got several steps closer to the front. Workers there unloaded the trucks, secured the cargo on barges and, ultimately, sent it onward to Egypt by ‘tow,’ a steamer with seven or eight barges.

The scale of the disruption caused by the labor demands of military recruitment, increased food and timber production, and roadbuilding and maintenance was enormous. In 1942, the chiefs of Upper Nile and Equatoria (again) impressed more than 5,000 laborers to gravel the Yei-Juba Road. This was not enough. 2,000 more laborers were brought from the North, together with an Artisans and Works Company and two Pioneer Companies of the Sudan Defense Force, to build bridges and clear roads. The war so intensified the demand for labor that officials took to rounding up and arresting hundreds of ‘able-bodied men’ in order to put them to work as convicts. The Commissioner of Equatoria District found that ‘in some cases young men are having to do three separate months of conscript labour in Juba every year, and sometimes more.’[15]Commissioner of Equatoria Province to the Civil Secretary (EP/37.B.1, 9.1.1946) quoted in Salah El-Din El-Shazali Ibrahim, Peripheral Urbanism and the Sudan (PhD thesis, University of Hull, 1985), p. … Continue reading Juba town alone required almost 1,500 conscript laborers to manage 1,000 tons per day of cargo and 800 vehicles each month.[16]Salah El-Din El-Shazali Ibrahim, Peripheral Urbanism and the Sudan (PhD thesis, University of Hull, 1985), p. 130 This increase in forced labor produced lasting demographic changes. Between 1939 and 1941, the town’s male population rose from 600 to about 2,500.[17]Governor-General’s Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1939-41 (inclusive), 190. Another 1,200 or so men enlisted in the Sudan Defense Force. And perhaps 500 joined the King’s … Continue reading

More than ever before, Juba’s importance as a port of transit, a commercial center, and focus for administration in southernmost Southern Sudan, made it an essential link in the Allied chain of communications and transportation. Writing for Great Britain and the East in October 1948, a correspondent summed up twenty years’ developments in the town in an article entitled ‘Juba Puts Itself on the Map.’ The town was so new, the author said, that ‘you may not find it on quite good maps of Africa, while even on the very best maps it will probably still be shown along with several sister towns, whose importance Juba has long since eclipsed: Mongalla, Gondokoro, Lado, Rejaf.’ [18]Anon., “Juba puts itself on the Map,” Great Britain and the East (October, 1948), 38 The scale of change—the influx of people, the churches and mosques, schools, a 300-bed hospital, an aerodrome, the introduction of electric light and filtered water supply, the election of an advisory town council, the congestion of vehicles, dust and livestock—that came from the work of coordinating ‘a vast army’ of troops and laborers and the daily arrival of a thousand tons of cargo on lorries from Congo, meant that Juba was not only a noteworthy place in the mid-forties but also a permanent one.[19]Arthur Charles Beaton, Equatoria Province Handbook: Equatoria province (Khartoum, Sudan, 1951), 27.

It is not hard to understand why this was also a period of labor unrest. Juba’s population doubled (from 4,135 to 8,265) during the four years following the end of the Second World War. Land allocated for ‘native housing’ was expanded: first Kosti, then (Hai) Malakal, Nimira Talata and Hilla Jallaba. Now workers were struggling to make ends meet. In his account of the formation of the Southern Sudan Welfare Committee and the 1947 strikes in Southern Sudan, Peter Garretson provides a table showing the rising cost of living in a southern town: in Juba, between 1938 and 1948, the price of dura increased by 283 percent; the price of meat and firewood increased 500 percent; rent increased 310 percent.[20]Peter Garretson, “The Southern Sudan Welfare Committee and the 1947 Strike in the Southern Sudan,” Northeast African Studies 8, no. 2/3 (1986), 183-4. Cloth was unavailable except at very high prices.

To get by, urban residents developed modes of mutual aid and assistance. As a result, the end of the Second World War came to coincide with a wider transformation of the colonial public sphere in Juba. Town residents made their neighborhoods livable by forming small sanduq (‘box’) saving schemes and rotating credit groups, sports teams, social clubs, and home-town organizations. These years also saw the growth of new forms of association outside the direct control of the colonial state: around beer shops, coffee stands, hashish parlors, dance halls, and football teams. These associations afforded opportunities for friendship, socializing, entertainment, advice, assistance, discussion and debate, and provided models for formal political organizations. Southern political parties were made, Christopher Tounsel has suggested, as much on the soccer pitch as in schools and colonial offices.[21]Christopher Tounsel, “Before the Bright Star: football in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018), 735-753. An adequate political history of South Sudan should focus not only on ‘the educated’ and the South Sudan Welfare Committee (SSWC), but also ordinary South Sudanese and the informal associations by which people scraped together enough to get by.[22]This view of informal urban space as an arena of civil society has been taken up by a number of scholars. Nicki Kindersley, The Fifth column? An intellectual history of Southern Sudanese communities … Continue reading

The Second World War connected Juba more firmly to other parts of Sudan. It had also helped to make status and regional differences more vivid. In his memoir of the period, Severino Fuli Ga’le describes a visit to a southern official’s grass-roofed house in Nimira Talata, which stood just a few hundred meters south of the ‘better built “Attala-Quarters” of the northern porters who worked on the Juba quay.’[23]Severino Fuli Boki Tombe Ga’le, Shaping a Free Southern Sudan: Memoirs of our Struggle 1934-1985 (Pauline, 2002), 18, 140. (Even better paid northern officials large houses were roofed with iron-sheet.) Long-standing and sharp differences in pay scales for Southerners and Northerners became a major source of grievance for ‘Article II’ staff, who were named after the pay scale classification for South Sudanese. Severino describes the heavy debts that he incurred to establish an independent family with his wife, Rozana Gune, and how ‘the cost of living for [Juba’s] inhabitants rocketed to unprecedented heights.’[24]Ga’le, 2002, 18 & 139. In those days, Article II class I staff received E£ 1.5 per month, much less than the E£ 2.5 that Peter Garretson suggests was necessary for a single man to cover basic living expenses in Juba.[25]Ga’le, 2002, 136-137.

It took a great deal of organizing, and confrontational protests, partly inspired by the example of wartime work stoppages and railway strikes in Atbara and Mombasa, to compel the colonial government to raise wages and to address discrepancies between Northern and Southern pay scales. In October 1947, striking Sudan Medical Service workers, Province headquarters clerks, and Posts & Telegraph trainees were joined by other workers, including the police, in picketing roads around Juba town, the Yei road, the crossing at Khor-Bou, and the road from the Native Lodging Area. Sympathetic strikes were organized in Wau, Rumbek, Tonj, and Yei with the help of the South Sudan Welfare Committee, whose members shrewdly interceded with officials to represent the strikers.

The strikes were organized in “Nimira Talata,” a neighborhood named after its class designation, and the Native Lodging Areas, where southern students and junior officials met to compose telegrams and discuss their demands. All this work organizing people of varied backgrounds drew on social habits developed by residents of the town’s popular quarters to make them livable and has often been eclipsed in official records by events like the strikes of 1947. Still, colonial officials also worried about what residents might be getting up to. In March of 1950, R.G. Dingwall, the District Commissioner of Juba, drawing on long-standing fears of ‘detribalization,’ complained that though the town council had approved a police post, butcher’s shop, and vegetable market for the Native Lodging Area, work had been stalled by the absence of the town surveyor: ‘The Native Lodging Area, which has extended its area considerably in recent years, is two miles from the police post and main Juba market. The population is losing its tribal ties and is badly organized. It is desired to restore discipline to it by (a) improving amenities and giving the population a higher standard and improving supervision and control.’[26]R.G. Dingwall, 1950, “Market and police post sites in NLA, Juba,” March 29th, 1950. (JUB JD/38/G/2)

Memoirs of post-World War II Southern Sudan like Severino Ga’le’s describe a time of intense intellectual activity alongside much organizational labor in a growing town. Juba had wide streets and many buildings, a busy wharf and an aerodrome, but beyond that, by the late 1940s, it had developed a character, a distinct way of getting along, which certainly had something to do with the conditions of its establishment but more to do with ordinary residents and the likes of Karisyo Ludoru, Daniel Jumi Tongun, Marako Rume Morgan, Nicola Obwaya, Placido Laboke, Chuol Macot Lual—the young students and junior officials arrested as the purported ringleaders of the 1947 strike in Juba. This period, with the transformations worked on Juba by the Second World War and the organizing labors of ordinary residents, has often been overshadowed in accounts of South Sudan’s history by a war that had not yet begun. It wouldn’t be overdramatic to say that Juba was vital to the Allied victory, or that ordinary South Sudanese established Juba as an enduring place by working together to make it livable; at the very least, the period is an important one in the making of Juba.

-Brendan Tuttle

References

| ↑1 | J. N. Richardson, “Bari Notes,” Sudan Notes and Records 16, no. 2 (1933), 181-186. |

| ↑2 | C.H. Piercy, 1966, Public Works in Equatoria Province 1928-1938 (SAD 298/4/2). Governor-General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1928, pp. 139-140. The village is referred to as “Nobari” or “Juba Nubary” in documents in the 1950s, during discussions about how to compensate its residents, who had been relocated by Province Authorities in 1930 and 1934. JUB EP/38/A/5 (Vol. I, 1949/56), 112-114. Juba Town Lands Scheme, 1947. “Juba Land Settlement,” “Judgement,” & “List of Persons Entitled to Land in Juba Nubary,” 23rd November, 1950. See also: Shuichiro Nakao, “A history from below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927–1954,” The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 31 (2013),139-160. |

| ↑3 | This road came to be known as the “Route Royale” after it was used by King Albert of the Belgians to make his way to the Congo to open the Albert National Park. |

| ↑4 | Governor-General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1928, pp. 139-140. |

| ↑5 | Yellow Fever was detected in South Sudan in 1933. Officials considered moving the aerodrome, but no other suitable place could be found. To prevent the spread of Yellow Fever, a residential cordon of 3km was established around the landing area. O. F. H. Atkey, ‘Sur les mesures qui seront prises au Soudan Anglo-Égyptien pour réaliser dans les aerodromes de Juba et de Malakal les conditions requises pour les aerodromes anti-amarils,’ Bulletin de l’Office International d’Hygiene Publique 27 (1935), 2377-9. Governor-General’s Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1934, p. 79, 126. |

| ↑6 | Governor-General’s Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1930. p. 136. |

| ↑7 | L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), 7. |

| ↑8 | J.N. Richardson remarked that two years after the town had been established, ‘the local population … still take little interest and have to be persuaded to supply the inhabitants with eggs and fowls, etc. [and] there is no suggestion that any want to move their villages nearer to Juba, so as to be at hand for the market.’ J.N. Richardson, “Bari Notes,” Sudan Notes and Records 16, no. 2 (1933), p. 184. Imposing taxes was a convenient way for colonial authorities to ensure that residents of Juba’s hinterlands had a compelling need for money. By 1941, Juba town required “the whole purchasable surplus of the Juba District to feed it.” Governor-General’s Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1939-41 (inclusive), p. 191. |

| ↑9 | Helen Foley, Letters to her Mother: War-time in the Sudan 1938-1945 (Castle Cary: Somerset, 1992), 40. |

| ↑10 | C.R. Williams, Wheels and Paddles in the Sudan (1923-1946) (Petland Press: Edinburgh, 1986), 100 |

| ↑11 | Anon., “The Growth of Juba,” Great Britain and the East (December, 1945), 42 |

| ↑12 | Anon., “The Growth of Juba,” 42 |

| ↑13, ↑19 | Arthur Charles Beaton, Equatoria Province Handbook: Equatoria province (Khartoum, Sudan, 1951), 27. |

| ↑14 | J.M. Pett & Geoffrey Pett, White Water Landings (Princelings: Norwich, 2016), 166. For comparison: during 1940 the Sudan Medical Service inspected and cleared of insects only 64 aircraft in Juba; in 1941 Medical staff inspected 1,014, or sixteen times the number of aircraft. H.A. Crouch, Public Health and Hygiene, Sudan Medical Service, Report of the Sudan Medical Service (Khartoum, 1941), 18. |

| ↑15 | Commissioner of Equatoria Province to the Civil Secretary (EP/37.B.1, 9.1.1946) quoted in Salah El-Din El-Shazali Ibrahim, Peripheral Urbanism and the Sudan (PhD thesis, University of Hull, 1985), p. 130. |

| ↑16 | Salah El-Din El-Shazali Ibrahim, Peripheral Urbanism and the Sudan (PhD thesis, University of Hull, 1985), p. 130 |

| ↑17 | Governor-General’s Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1939-41 (inclusive), 190. Another 1,200 or so men enlisted in the Sudan Defense Force. And perhaps 500 joined the King’s African Rifles and travelled as far afield as India, Burma, and Ceylon. |

| ↑18 | Anon., “Juba puts itself on the Map,” Great Britain and the East (October, 1948), 38 |

| ↑20 | Peter Garretson, “The Southern Sudan Welfare Committee and the 1947 Strike in the Southern Sudan,” Northeast African Studies 8, no. 2/3 (1986), 183-4. |

| ↑21 | Christopher Tounsel, “Before the Bright Star: football in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018), 735-753. |

| ↑22 | This view of informal urban space as an arena of civil society has been taken up by a number of scholars. Nicki Kindersley, The Fifth column? An intellectual history of Southern Sudanese communities in Khartoum, 1969-2005 (PhD dissertation, Durham University, 2016); Ahmad Alawad Sikainga, Slaves into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan (University of Texas Press: Austin, 1996), 161-65; Christopher Tounsel, “Before the Bright Star: football in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018), 735-753. |

| ↑23 | Severino Fuli Boki Tombe Ga’le, Shaping a Free Southern Sudan: Memoirs of our Struggle 1934-1985 (Pauline, 2002), 18, 140. |

| ↑24 | Ga’le, 2002, 18 & 139. |

| ↑25 | Ga’le, 2002, 136-137. |

| ↑26 | R.G. Dingwall, 1950, “Market and police post sites in NLA, Juba,” March 29th, 1950. (JUB JD/38/G/2) |

gumbo-sherikat,

Hai Gabat,

Hai Malakal,

Hai Malakia,

Juba International Airport,

Juba Nile Bridge,

Juba town,

Juba Town Hai Jallaba Mosque,

Jubek's Grave