Juba in Maps, 1938 – 1949

In 1940, Juba had an official population of about 1,600 people, comprising 57 European Government officials, missionaries, and traders, 132 Northern Sudanese officials and traders, 27 Egyptians, and 1,397 Southern Sudanese “subordinate Govt. employees and local labour,” in the phrase of a military handbook of the time. There were at least 4 private cars and 15-20 commercial lorries.[1]Great Britain (Army) (1940) The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: handbook of topographical intelligence (Khartoum: General Staff, Intelligence Branch), pp. 67-8. Juba grew rapidly during the next five years, when the town was an important link in the African Forces Line of Communication (AFLOC), the military supply line that connected the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States to Cairo and the North African campaign.

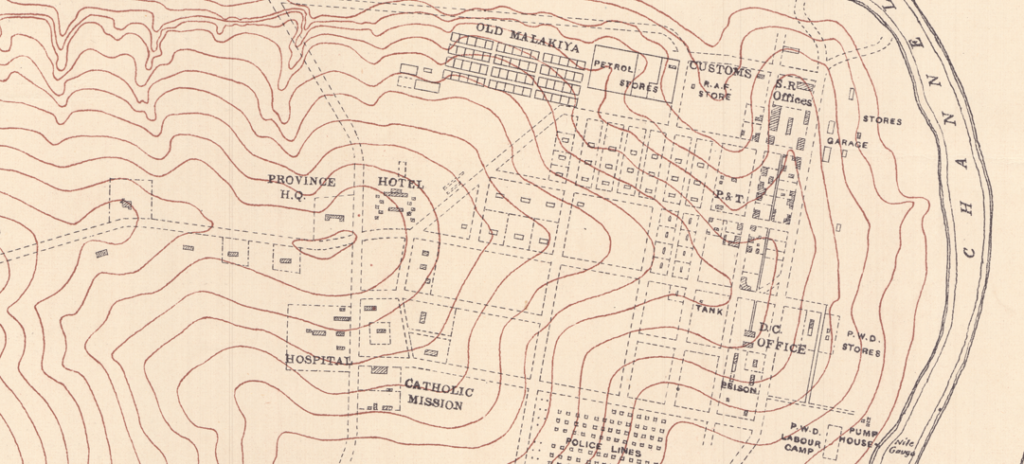

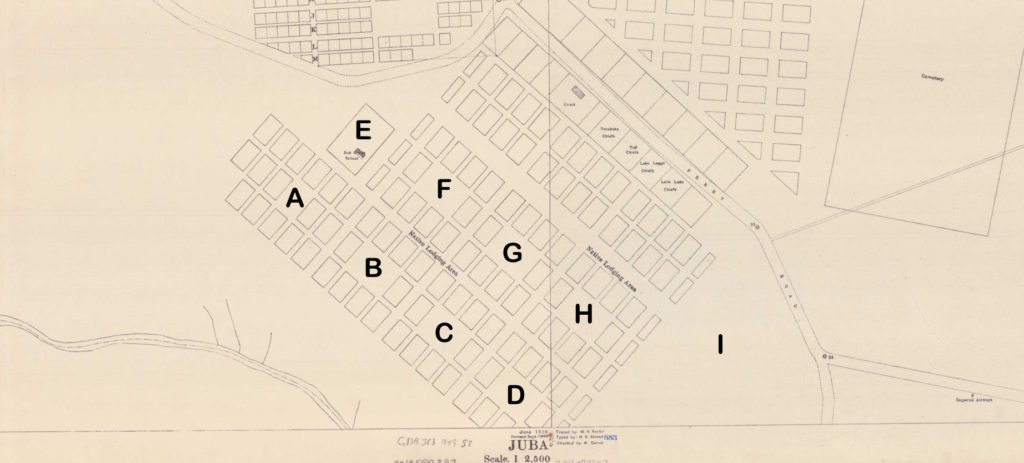

Four years after the Second World War, in 1949, when these maps were published, the town’s population had reached more than 8,265 and the hierarchy of colonial society was plainly visible in the plan of Juba. The Governor’s “large house” was located “about 200 feet above the river level,” at town’s highest point, making a prospect from which one could “command an extensive view of the surrounding country.”[2]The house was completed in September 1930. Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1930 (1930), pp. 153. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Handbook of Topographical Intelligence … Continue reading On the town’s summit, along the high ridge where Ministries Road runs today, were the wireless transmitting station, the residences of senior British officials, and the Provincial Headquarters. Rotating clockwise around the flagpole in front of the Province HQ, the Juba Hotel, the Société du Haut Uele et du Nil (or SHUN), the Southern Sudan Bookshop, and the Hospital lay at a similar elevation. The Catholic Mission, located just southeast of the hospital, had required an exception to the Mission Spheres policy to establish a headquarters there.[3]Located on the west bank of the Nile, Juba falls in a CMS zone. In 1927, Eastern Equatoria was made an autonomous Apostolic Prefecture, which is a kind of ecclesiastical district under the … Continue reading To the east, down the hill from the Province HQ and Memorial stone, were the bigger houses of business, junior officials’ residences, bachelors’ quarters, the streets where merchants lived behind their shops, the Native Officials Club, the Post & Telegraph Office, the district headquarters (the merkaz), the vegetable market, and the police lines; at the town bottom, beside the river, were the warehouses and workshops, petrol stores, wharfs, and mills. To the north, a small village called Juba Nabari, (where many of the area’s original inhabitants had been forced to relocate), lay on riverbank to the east of the Juba Forest Reserve.[30]This settlement was inundated in the early 1960s and abandoned by its residents. Susan Jenkins (1981) Aspects of the informal economic sector of Juba southern Sudan (PhD Dissertation, Durham … Continue reading To the south, the Power House and pumping station (completed in 1939) provided electricity for lights and fans to houses, offices, and shops and a filtered water supply to the town’s sanitary district.

Juba was divided into two parts by Khor Bau, the small stream that, today, runs between the Hai Malakal Cemetery and the Stadium before flowing into the Nile near the Afex River Camp hotel. To the north of Khor Bau, it was mostly whitewash, brick, stone, and galvanized-iron roofs where Juba’s senior officials’ residences, official buildings, factory areas, and commercial districts were laid out. Malakia, with its mud-thatch houses in clean-swept yards, lay to the south. “As one passes from one [side of Juba] to the other,” the journalist Anthony Mann remarked during his visit to Juba in the mid-1950s, “it is difficult to realize one is in the same town.”[5]Anthony Mann, Where God Laughed: The Sudan Today (London: Museum Press Limited, 1954), p. 113.

The plan of Juba was designed to set colonizers and colonial subjects apart, but the practical logistics of empire required these groups to live close together.[6]Admittedly, Juba was an usually spread-out government station. The Governor’s house situated on the town’s highest point, about one and a half miles from the river. Earlier Government stations, … Continue reading Starting in 1927, former slave soldiers were transferred to Juba from Mongalla, Gondokoro, and Rejaf and officials instituted a kind of corvée system by which area chiefs were forced to provide laborers on a monthly basis to do the work of building the town. This system of forced labor led to the settlement at Burusoki, a residential quarter of about 1,000 people laid out to the south of the aerodrome. Burusoki’s residents were abruptly transferred to a new “Native Lodging Area” in 1934, when the Juba landing ground was made into an anti-amaryl aerodrome as a precaution against the spread of Yellow Fever. A nearly three-kilometer residential cordon for those designated as “natives” was established around the aerodrome and Burusoki’s residents were resettled on the site of today’s Malakia neighborhood, which comprised eight blocks of 70 houses and is indicated on the map as the Native Lodging Area. This move helped to entrench Juba’s racialized residential segregation, which, together with the strict social hierarchies that organized the town’s offices, worksites, and places of commerce and leisure, enabled senior European officials to maintain social distance in a setting characterized by regular physical proximity.

Maps like this one were also made to accomplish another separation. Where officials could rely on whole truckloads of soldiers and police to back up their decisions, land surveys allowed administrators to cut through the complicated attachments, overlapping uses, claims and counter-claims, family histories, and varied narratives that developed around any place where people lived in the country. By the late 1930s, officials could simply order people to clear out, secure in the knowledge that everyone understood that refusing such an order would be an open challenge to colonial authority and invite a large number of soldiers to show up. Maps helped administrators and officials to make decisions about land use “at the drawing-table,” by consulting paper maps in their offices, far from the people affected by the decision. In this way maps helped to widen the gap experienced by many between “Government” and “the community.”[7]These categories, “Government” and “the community” were co-constituted, of course, partly by practices of separation, partly by people defining themselves against the violent and racist … Continue reading

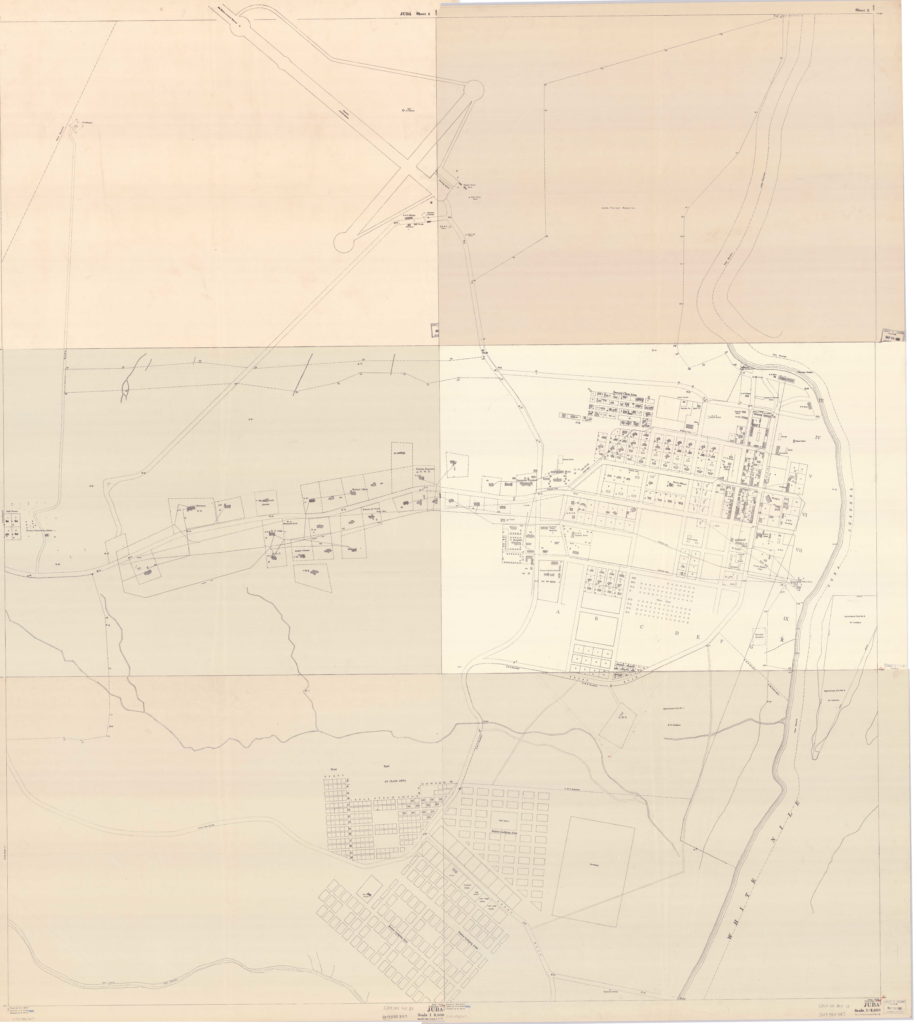

Between 1856 and 1950, the Sudan Survey (Maṣlaḥat al-Misāḥah) produced a series of country-wide, small-scale 1:250,000 maps, all manner of thematic maps (rainfall, population movements, agricultural regions, wildlife habitats, animal densities, “tribes” and languages, and so on), and large-scale town maps.[8]Cartographers use the terms “large scale” and “small scale” to refer to the representative fraction, the relation of a given “unit” on a map to “units” of the same type on the ground. … Continue reading The large map (Fig. 1) comprises six 1:2,500 maps that have been stitched together.[9]Revisions to the Juba town survey were completed in 1936, when a surveyor was posted to the Southern provinces, and level surveys for drainage schemes were made. These maps were published in 1938. Each 60 x 80 cm map is mounted on rough cloth and held by the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

These are lovely maps. But their precision and apparent detail can be misleading. A great deal has been left out. These maps show municipal boundaries, residential blocks and plot numbers, roads, an aerodrome, official buildings, and two forest reserve areas. They do not show tukls or the pathways and alleys that connect them, nor the courtyards where people relaxed or shared meals. Homesteads within town boundaries are not shown, creating the impression that the area was uninhabited by anyone whose residence there had not been fore-planned and authorized.[10] Officials routinely evicted people and burned their houses down to discourage them from living in places that had not be authorized by those officials. Places for collecting water are not shown. There is no indication of the color of the soil or the rocks. Places that become marsh during the rainy season are not shown. There are no features suggesting pre-colonial occupation of the area. Two sacred rocks, Pita and Kaku, are not present on the map. These are not simply blank spaces. They’re deliberate omissions.

These omissions allow the map to present a story of imperial accomplishment. A map like this is a fantasy of perfect control and correspondence between plans and their realization. It shows an aerodrome, a 167-bed hospital, “a modern hotel,” and provincial offices together with “first-class roads” and water pipes spread out on open ground, as if the area had been uninhabited prior to 1928, when the first stones were laid for the Sudan Railroads and Customs offices (S.R. Office Customs Office on the map) to prepare for the steamer service.[11]C.H.Z. Piercy, “Public works in Equatorial Province, 1928-1938” (letter to Richard Hill, 2 Mar 1966, SAD.298/4/4). Indeed, this is the story told by John N. Richardson, Deputy Governor of Mongalla Province, in “Bari Notes,” a short account of the founding of Juba published in Sudan Notes & Records one year before the Province Headquarters was transferred there: “The town of Juba is one of the few towns in Africa, which has been planned and built without any necessity of paying compensation to original inhabitants and without the handicap of having to make a new town fit with the old town or village.” [12]J.N. [John Noel] Richardson, Bari Notes. II Juba, Sudan Notes and Records 16, part 2, (1933), pp. 183.

This was not true, of course. There were scattered homesteads and a handful of Bari villages in the vicinity of the site that had been chosen for Juba when it was surveyed in 1927.[13]That people in the area tended to live in scattered homesteads, rather than compact villages, perhaps made it easier for authors like Richardson to represent the area as terra nullius. One of these was called Juba—at least by George O. Whitehead, who was attached to the C.M.S. Nugent Mission School there, which at the time lay on the outskirts of the village.[14]The CMS Nugent Mission School was established in 1920 and comprised a “house, school, church, workshop, and about twelve huts for boys.” The school was relocated to Loka in 1930. Christopher … Continue reading Richardson remarks, “the village of Juba … contained some 36 homes [or about 130 adults] under Magara as headman,” at the time “[w]hen the Government told them they would have to clear out” (p.186).[15]Richardson, Bari Notes, p. 184, 186. Roger Hill gives an average occupancy rate of 3.58 persons per tukl for 1978/9. Roger Hill, (1981) Migration to Juba: a case study, Durham theses, Durham … Continue reading One does not imagine that they were particularly happy about being forced to pick up and move without compensation in order to make space for the construction of Government offices.[16]Settlement Officer, Juba. “Judgement,” 23 November 1950. Juba Town Scheme, 1947. [Juba archives] 38/A/5 – 113. Several other villages have been …. By Juba’s expansion… Indeed, Whitehead described how the “clear out” led the community to split into two: when the residents of the village were made to leave, some of the older men consulted a diviner, who argued against that a site previously chosen by Magara on the grounds that “the ground was bad,” Whitehead said. “[T]hough the bulk of the village followed the [diviner’s] advice, and chose a site by the river bank,” (presumably to Juba Nabari), Magara, his brother, and their families went their own way.[17]This story provided by Whitehead is given by the Seligmans to illustrate “the independence of outlook in religious matter” characteristic, they say, of this part of the Nile Valley, where though … Continue reading

The legacy of imperial rule remains clearly visible in contemporary Juba. Though the city has seen great demographic and physical expansion, (particularly, after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005), Juba has broadly developed along the lines established in the 1940s. The first-class housing laid along Ministries Road for senior British officials remains an area of spacious buildings, which house government ministries and officials, ambassadors, and the residences and offices of the South Sudan’s largest international organizations. The town’s old commercial quarter, which was occupied by Northern Sudanese, Egyptians, Cypriots and Greeks, Italians and Maltese, Lebanese, Syrians, Indians, and Pakistanis, and other foreigners, remains a cosmopolitan and important center of commerce. Residents of the Native Lodging Area (today’s Malakia) saw minimal investment in infrastructure or amenities as the area was extended in the 1930s and 1940s to comprise Kosti, Malakal, Nimr Talata, and then Hilla Jallaba, much as residents of the present city’s largely self-governing residential suburbs must often make do with what they can build themselves. Indeed, as the historian Cherry Leonardi has pointed out, this aspect of the growth of Juba recalls even older patterns: “[s]uch concentric patterns of settlement around the town [as Juba’s suburbs] reveal the replication of the zariba patterns of the nineteenth century.”[18]Cherry Leonardi, Dealing with Government in South Sudan (James Currey, 2015), pp. 82-83.

Points of Interest

SHUN. The Société du Haut Uele et du Nil, or SHUN, was a trade concern and transportation service established in Aba in 1924 to link the Belgian Congo and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. It was directed in Juba by Nikolaus Metaxas (1879-1946), who, during the First World War, had built up a profitable business exporting Egyptian cotton byway of the Rejaf-Aba Road through the Belgian Congo. In Juba, SHUN provided regular car service for passengers travelling between Aba and Juba.[19]C.H.Z. Piercy, “Public works in Equatorial Province, 1928-1938” (letter to Richard Hill, 2 Mar 1966, SAD.298/4/3). Richard Hill, A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan, 2nd ed. (Taylor & … Continue reading

The Southern Sudan Bookshop was stocked with school texts and various Christian reading materials, including hymn and prayer books and portions of the old and New Testament scriptures in Bari, Moru, Azande, Dinka, and other languages. The bookshop was later re-named the Apaya Bookshop after Canon Andarea Apaya, “one of the first two Sudanese ordained in the Episcopal Church.”[20]He was ordained in 1941 and served mainly in Lui until his death in 1966. Kuyok Abol Kuyok. South Sudan: The Notable Firsts . AuthorHouse UK. Kindle Edition. Roland Werner, William Anderson, Andrew … Continue reading

Forest Reserves. Two forest reserves are present on these maps. The Juba Reforestation Area was a forest of 152 feddans that lay to the south of the Wireless Transmission Station in the triangular area formed, today, by Ministries Road, University Road, and Unity Avenue. The Juba Forest Reserve lay along the river and to the east of the aerodrome and north of Juba town. This forest reserve helped to meet demands for firewood for bakeries, tobacco curing, and other uses in the growing town.

Native Officials Club. The Native Officials Club was built in 1936. It had been put forward, an official wrote, “on both social and health grounds.” No existing building was then available and the justification given for building a club is revealing of Juba’s housing conditions in the late-1930s: “At present the native officials have nowhere to go in the evenings except their own very unattractive houses and as a result tend to sit in the street outside a shop where they are heavily bitten by mosquitoes. There is a very definite demand for a building of this kind, which will be intensified by the increase of staff resultant on the province amalgamation.”[21](Juba Archive) EP/9/B.1 p.88. P.W.D. Form No. 1. 1936 Building programme. Province Buildings. Native Officials Club.

Native Lodging Area. Juba’s population grew during the winter and spring each year with the arrival in the Malakia of a floating stratum of itinerant petty traders, craftsmen, domestic workers, porters and other casual laborers, family members and various guests and other visitors. Colonial officials viewed this migration to town “as an evasion of chiefly authority”—in the Cherry Leonardi’s phrase—and a loosening of “rural social control,” which, officials believed, would lead to people becoming discontented and rebellious.[24]The scale of forced and conscript labor grew to such proportions during the Second World War that many chiefs in the vicinity of Juba reported that their “subjects had run away.” Leonardi, Cherry … Continue reading Officials thus sought to maintain sharp social and physical boundaries between the town and the surrounding countryside.[25]Cherry Leonardi, Dealing with Government in South Sudan (James Currey, 2015), p.82 Each April, when the rains began, officers made their way through Juba, rounding people up, loading them into government lorries, and ‘despatch[ing] them … to their home centres’ to begin farming.[26]L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), p.7.Those who were permitted to live within the town boundaries were assigned to “Native Lodging Areas,” cordoned districts placed outside official town housing schemes, where they were not entitled to any amenities such as water or electricity. Not having title or tenure, residents’ precarious housing situation under a temporary tenancy system helped to ensure that they supplied cheap and easily controlled labor to colonial authorities who could arrest them or turn them out at any time.

The Juba Malakia of the 1940s comprised the Malakia Primary School and seven residential blocks, each of which were divided into ten plots demarcated by castor oil trees. Each block was organized under a chief, partly in an effort by officials to maintain what they believed to be customary modes of “traditional authority.” While this arrangement in Juba strongly recalls rural patterns of Indirect Rule, Ahmed Alawad Sikainga points out that seeing this urban system as being modelled on rural Native Administration gets history the wrong way around. The techniques by which British officials violently reordered space in Juba so that they could see South Sudanese people as culturally and emotionally distant, or represent them on a map, for example, were developed first in close physical proximity. [27]Visitors to the town in the 1930-1950s sometimes remarked that the Malakia seemed to have been put there to provide tourists with a view of what Livingstone, Stanley, Speke, Grant, or Baker had seen. … Continue reading Sudan’s first “Native quarters,” the Daims (“residential quarter”) of Khartoum, were settled by ex-slaves and reorganized under “Sheikhs” when Khartoum was rebuilt as a sanitary city along “European lines” during the earliest years of Anglo-Egyptian rule.[28] In 1902, E.A. Stanton described how any Sudanese “who were not either house holders or living with their employers [were] turned out and made to live in the large native village outside the lines … Continue reading The policy that came to be known as of Native Administration and was later applied to rural areas, in the 1920s, partly in response to the problem of having too few trained administrators, was first developed in towns.[29]Ahmed Alawad Sikainga, Slaves into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), pp. 76-81, 92

Brendan Tuttle

References

| ↑1 | Great Britain (Army) (1940) The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: handbook of topographical intelligence (Khartoum: General Staff, Intelligence Branch), pp. 67-8. |

| ↑2 | The house was completed in September 1930. Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1930 (1930), pp. 153. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Handbook of Topographical Intelligence (1940), pp. 66-68. From this vantage, one could see “the tops of the grass roofs of the malakia.” Peter Molloy, The Cry of the Fish Eagle (London: Michael Joseph, 1957), p. 17. |

| ↑3 | Located on the west bank of the Nile, Juba falls in a CMS zone. In 1927, Eastern Equatoria was made an autonomous Apostolic Prefecture, which is a kind of ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a prefect (rather than one like a diocese or bishopric, which is under a bishop). Giuseppe Zambonardi (1884-1970) was appointed Prefect and took up residence in Juba. The Roman Catholic Mission built a headquarters in Juba in 1934, and Saint Joseph’s Church was opened by 1935. The British Government demanded Zambonardi’s replacement by a non-Italian following the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Zambonardi left in 1938 and was replaced by Stephen Mlakić (1884-1951), who was born in Austria-Hungary (in Fojnica, Bosnia) and worked in Khartoum (1920-1927), Port Sudan (1931-1933), Yoynyang (1927-1931, 1933-1937), Malakal (1937-1938), and Juba (1938-1950). Fr Francesco Chemello, A Long Love Story: The Comboni Mission in South Sudan, from the beginning 1857-2017 (Bibliotheca Comboniana, 2017). P. Francesco Chemello, Una Grande Storia D’Amore (Bibliotheca Comboniana, 2021). Fr. Francesco Chemello, The Comboni Missionaries in South Sudan: An outline history (Fondazione Nigrizia Onlus, 2017). In those days there were Catholic missions in Rejaf, Torit, Isoke, Palotaka, Okaru, and Kapoeta. |

| ↑4 | A surveyor was first posted to Sudan’s southern provinces in 1936. During that year the first Juba town survey was completed. Governor General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan (1936), p. 73. |

| ↑5 | Anthony Mann, Where God Laughed: The Sudan Today (London: Museum Press Limited, 1954), p. 113. |

| ↑6 | Admittedly, Juba was an usually spread-out government station. The Governor’s house situated on the town’s highest point, about one and a half miles from the river. Earlier Government stations, which were built before colonial terror campaigns had reassured officials that they would not be attacked, were often more compact. By the 1930, motor roads had been completed and motorized transport to and from offices had become common practice. These factors combined to allow a more spread-out town to be planned and built. C.H.Z. Piercy, “Public works in Equatorial Province, 1928-1938” (letter to Richard Hill, 2 Mar 1966, SAD.298/4/2). |

| ↑7 | These categories, “Government” and “the community” were co-constituted, of course, partly by practices of separation, partly by people defining themselves against the violent and racist logics of empire. Other political dichotomies (such as between moral logics of the town and the village) were also overlaid on this division. But much as power was founded on these oppositions, they were never wholly complete. Even surveys were not always detailed enough to “enable a plan to be drawn at the drawing-table.” In the “Northern Second Class Area,” for example, small plots were laid out in a grid without reference to outcrops of rock or the slope of the land. In 1950, S.R. Simpson, the Commissioner of Lands and Registrar General, suggested that the planner and surveyor work together, pegging out lines which roads would follow and marking off plots in “various shapes and sizes.” S.R. [Stanhope Rowton] Simpson, Notes on Various Problems in Juba, Khartoum 15 June 1950, p. 4. Juba Archive, 38/8/5 – 15. |

| ↑8 | Cartographers use the terms “large scale” and “small scale” to refer to the representative fraction, the relation of a given “unit” on a map to “units” of the same type on the ground. Thus a representative fraction of 1:2,500 means that 1 inch on a map represents about 206 feet or 0.039 miles on the ground and is a larger scale than 1:250,000 (where 1 inch represents about 4 miles), despite the later showing a larger area. |

| ↑9 | Revisions to the Juba town survey were completed in 1936, when a surveyor was posted to the Southern provinces, and level surveys for drainage schemes were made. These maps were published in 1938. |

| ↑10 | Officials routinely evicted people and burned their houses down to discourage them from living in places that had not be authorized by those officials. |

| ↑11 | C.H.Z. Piercy, “Public works in Equatorial Province, 1928-1938” (letter to Richard Hill, 2 Mar 1966, SAD.298/4/4). |

| ↑12 | J.N. [John Noel] Richardson, Bari Notes. II Juba, Sudan Notes and Records 16, part 2, (1933), pp. 183. |

| ↑13 | That people in the area tended to live in scattered homesteads, rather than compact villages, perhaps made it easier for authors like Richardson to represent the area as terra nullius. |

| ↑14 | The CMS Nugent Mission School was established in 1920 and comprised a “house, school, church, workshop, and about twelve huts for boys.” The school was relocated to Loka in 1930. Christopher Tounsel, Chosen Peoples: Christianity and Political Imagination in South Sudan (Duke, 2021), p.29. |

| ↑15 | Richardson, Bari Notes, p. 184, 186. Roger Hill gives an average occupancy rate of 3.58 persons per tukl for 1978/9. Roger Hill, (1981) Migration to Juba: a case study, Durham theses, Durham University, p.218. Naseem Badiey (2014) records an alternative version of these events given by Tongung Lado Rombe, a Bari elder and Community Association Chairman: “[Juba] was built on the site of a Bari village called Tindu… and gained its name from the village chief who was called Jubé [or Jubek].” Naseem Badiey, The State of Post-conflict Reconstruction (James Currey, 2014), 38. Robin Mills says that the village was named after a rock outcrop in the river. L. Robin Mills, The People of Juba (University of Juba, Population and Manpower Unit, 1981), p.4. |

| ↑16 | Settlement Officer, Juba. “Judgement,” 23 November 1950. Juba Town Scheme, 1947. [Juba archives] 38/A/5 – 113. Several other villages have been …. By Juba’s expansion… |

| ↑17 | This story provided by Whitehead is given by the Seligmans to illustrate “the independence of outlook in religious matter” characteristic, they say, of this part of the Nile Valley, where though diviners may be “consulted in circumstances of doubt or difficulty,” others may disregard their advice. Charles G. Seligman and Brenda Z. Seligman, The Bari, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 58 (1928), 436. A photograph of Magara taken by Whitehead is included as Plate XLV. I am following Simonse (2008, p.371) by rendering ‘bunit as “diviner.” Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centralism and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan (Kampala: Fountain, 2018). |

| ↑18 | Cherry Leonardi, Dealing with Government in South Sudan (James Currey, 2015), pp. 82-83. |

| ↑19 | C.H.Z. Piercy, “Public works in Equatorial Province, 1928-1938” (letter to Richard Hill, 2 Mar 1966, SAD.298/4/3). Richard Hill, A Biographical Dictionary of the Sudan, 2nd ed. (Taylor & Francis, 2019), p. 238. Congo Belge, Annexes au Bulletin Officiel du Belgisch-Congo (1933), pp.626-630. |

| ↑20 | He was ordained in 1941 and served mainly in Lui until his death in 1966. Kuyok Abol Kuyok. South Sudan: The Notable Firsts . AuthorHouse UK. Kindle Edition. Roland Werner, William Anderson, Andrew Wheeler, Day of Devastation, Day of Contentment (Paulines, 2000), 496. Martin Marial Takpiny, Samuel E. Kayanga, Andrew C. Wheeler, Wesley Natana, “CMS Stations in Southern Sudan,” in “But God is Not Defeated!” (Paulines, 1999), 72. |

| ↑21 | (Juba Archive) EP/9/B.1 p.88. P.W.D. Form No. 1. 1936 Building programme. Province Buildings. Native Officials Club. |

| ↑22 | Nakao Shuichiro, A History from Below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927-1954. The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 31 (2013), p. 147. |

| ↑23 | First Population Census of Sudan 1955/56: Final report. Town planners’ supplement |

| ↑24 | The scale of forced and conscript labor grew to such proportions during the Second World War that many chiefs in the vicinity of Juba reported that their “subjects had run away.” Leonardi, Cherry (2005) Knowing authority: colonial governance and local community in Equatoria Province, Sudan, 1900-1956 (PhD dissertation, Durham University), p. 143. |

| ↑25 | Cherry Leonardi, Dealing with Government in South Sudan (James Currey, 2015), p.82 |

| ↑26 | L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), p.7. |

| ↑27 | Visitors to the town in the 1930-1950s sometimes remarked that the Malakia seemed to have been put there to provide tourists with a view of what Livingstone, Stanley, Speke, Grant, or Baker had seen. In those days, air passengers stopping overnight in Juba were given the afternoon to stroll along the town’s “pleasing water-front” or to visit a mission church or “native village.” Grace Crile, Skyways to a Jungle Laboratory: An African Adventure (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1936). |

| ↑28 | In 1902, E.A. Stanton described how any Sudanese “who were not either house holders or living with their employers [were] turned out and made to live in the large native village outside the lines of fortifications. Here the natives are divided into tribes, each of which had its own section under its own Sheikh, the whole being under one Head Sheikh.” E.A. Stanton, “Khartoum Province,” Governor General’s Report on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan (1902), p. 312. |

| ↑29 | Ahmed Alawad Sikainga, Slaves into Workers: Emancipation and Labor in Colonial Sudan (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), pp. 76-81, 92 |

| ↑30 | This settlement was inundated in the early 1960s and abandoned by its residents. Susan Jenkins (1981) Aspects of the informal economic sector of Juba southern Sudan (PhD Dissertation, Durham University), p. 33. |

Custom Bus Park,

Freedom Bridge,

Garang Mausoleum,

gumbo-sherikat,

gurei,

Hai cinema,

Hai Gabat,

Hai Malakal,

Hai Malakia,

Hai Neem,

jebel kudjur,

Juba International Airport,

Juba Nile Bridge,

Juba Stadium,

Juba town,

Juba Town Hai Jallaba Mosque,

Jubek's Grave,

kator,

konyo konyo market,

Lagoon Dumpsite,

Munuki,

nyakuron cultural centre,

river port,

Souksita,

un house-poc site,

University of Juba