It Is Time To Plant Good Words In People’s Hearts

Chief Simon Soro was born in 1926 in Rokon, a village located 80 km to the north-west of Juba. The son of a prominent chief, in the 1940s he came from Rokon to Juba, which was then a fairly new colonial town. He enrolled in school and growing up, he witnessed first-hand many aspects of the history and development of what is now South Sudan’s capital city. “I never left Juba” he said, including during the two civil wars that raged in South Sudan, from 1955 to 1972, and then from 1983 to 2005. In this archive, Chief Simon Soro recalls having lost a son in each of these conflicts – and to have “never held a gun in [his] life”. The video is divided into chapters, and for each chapter, historian Dr. Brendan Tuttle has written annotations that can help understand the context of what Chief Simon Soro is referring to. Further references are also included for those of you who would like to study all this further.

Duration: 35min45sec

Date of filming: 2015

Date of publication: 2024

Director, Camera Operator, Producer and Editor: Florence Miettaux

Interview: Loes Lijnders

Translation: Silvano Yokwe

Introduction & Chapter 1. “It was us who built Juba, with our bare hands…” Chief Simon Soro recalls a song expressing the feelings of labourers taken from their villages to build the city in the early 1900s.

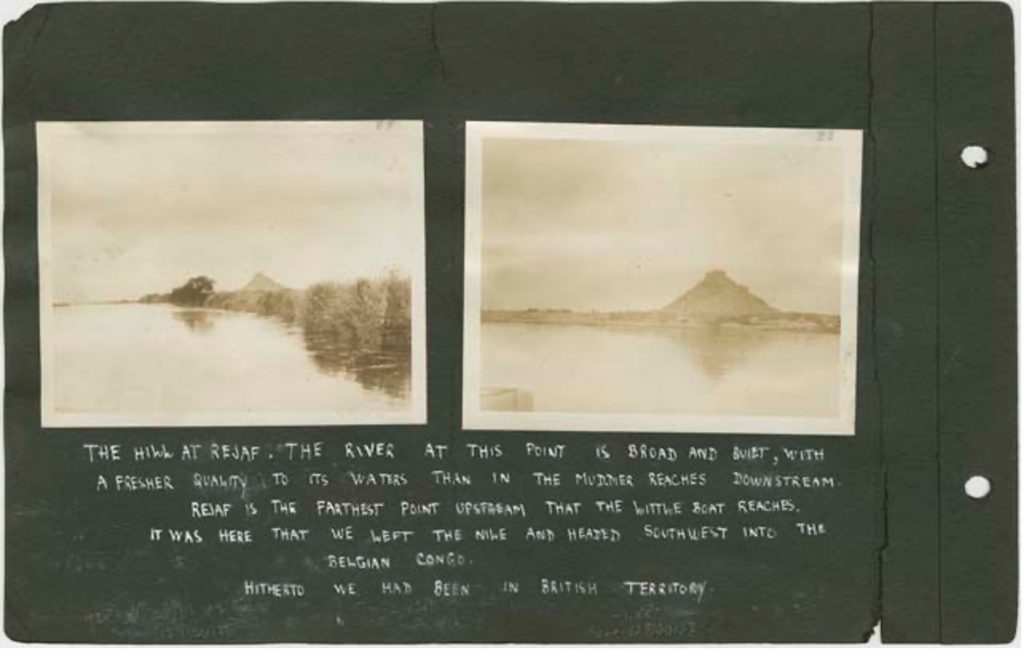

Chief Simon Soro’s account of the history of Juba begins with “a song from the time when the Belgians were in Rokon,” referring to the 13-year period between 1897 and 1910 when Belgian forces occupied the Lado Enclave, and describes how the people of Nyangwara were made to build the Belgian station at Loguek, the name of the tall hill that has since come to be called Rejaf. In the song the laborers lament, “When are we going to return to our village?” Next, Simon describes the slow growth of Juba. He begins with an image from the late 1920s in Juba that recalls the labors at Loguek, when Mundari, Nyangwara, Lokoya, and others from the surrounding countryside were rounded up to break the stones of Jebel Körök and use them to build Juba with their bare hands. “In those years, Juba was just a bush…” Chief Simon Soro says. He describes how the town was built up slowly. How independence came to the Sudan and the country was handed over in 1956 to “the Arabs,” who were educated. How there was quarrelling and conflict and “the disputes between the Southerners and the Arabs escalated,” eventually culminating in a war that ended with the Addis Ababa period (1972-1983) and the formation of the High Executive Council (HEC) to govern the autonomous region of Southern Sudan. This was followed by a second civil war and then the independence of the South.

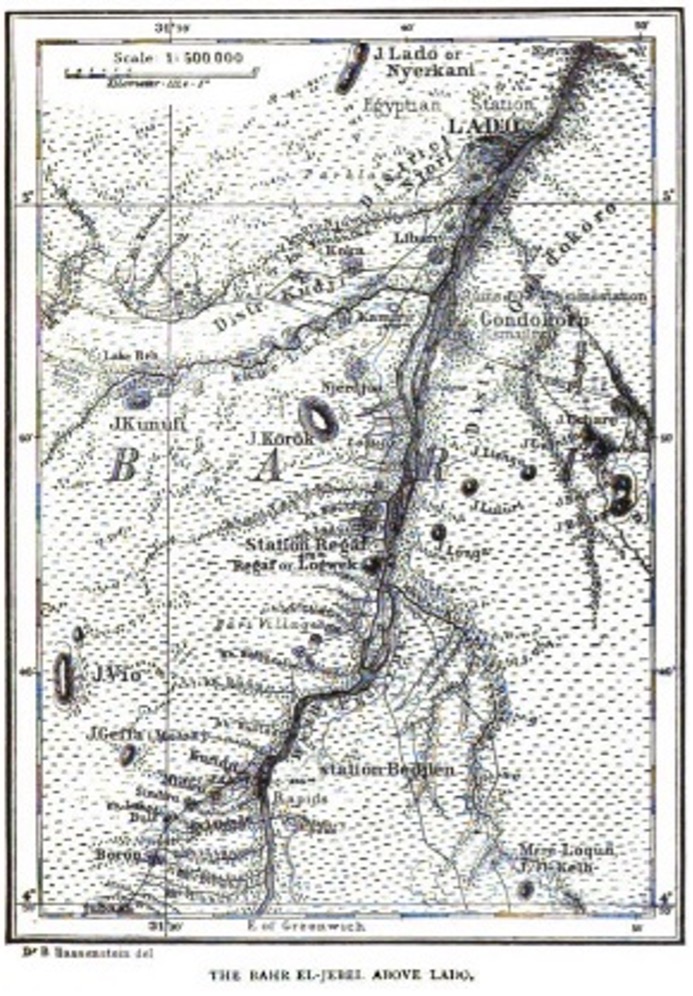

“…when the Belgians were in Rokon….” Rokon lies roughly 80 kilometers northwest of Juba on the Juba-Maridi Road. Belgians occupied the area from 1897 to 1909. This territory was called the Lado Enclave after Lado, a river port on the Nile, which like the nearby mountain was itself named after Chief Lado-lo-Möri. The Lado Enclave (c.1897–1910) was created by the Franco-Congolese Treaty of August 1894 but it was not until 1897 that the Congolese forces reached Rejaf. The particulars of the Enclave were the unanticipated outcome of an attempt by King Leopold II of Belgium to negotiate a treaty with Great Britain by which the Congo Free State would be linked to the Nile through Bahr al-Ghazal. The British government, which aimed to control an unbroken chain of possessions running from Cairo to Cape Town, hoped to impede French efforts to control territory stretching from Senegal to French Somaliland (present day Djibouti). However, under pressure from France, Leopold abandoned the greater part of Bahr al-Ghazal, retaining a smaller patch of territory, the Lado Enclave, which linked the Congo and Nile rivers. It was bounded on the north by Latitude 5° 30′ N. and on the west by that parallel’s intersection with meridian 30° East of Greenwich, a point that lies a little to the west of the Juba-Rumbek Highway in Mundri Payam; its southernmost extent reached to Mwitanzige or Lake Albert, far into present-day Uganda. The White Nile defined the Enclave’s eastern boundary.

See also: Map of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1904), showing the location and boundaries of the Lado Enclave.

“Bla bla bla, bla bla bla. Just drunk, foaming at the mouth. Talking anyhowly, not making any sense…” The imagery of drunkenness and foaming at the mouth may evoke trance, warriors screwing up their courage before entering a fight, or simply imply that the song is a drinking song.

Further reading: For a discussing of Nyangwara drinking songs, see A.C. Beaton, “Some Bari Songs,” Sudan Notes and Records 18, no. 2 (1935), pp. 277-287.

“Everyone protects [their] territory. The land cannot be grabbed anyhowly…” Simon Soro’s imagery of warriors massing like termites (“The women were ululating and the men were with their bows and arrows. They were ready to use them.”) may picture attacks made on Lado and Rejaf in 1885. “This talks about the Turkish soldiers,” Soro says. “The ones who came here to destroy us.”

In late-1885, Turco-Egyptian government stations in Equatoria faced what seemed to be a “revolt of the entire Bari population.”[1] Wilhelm Junker, Travels in Africa during the years 1882-1886, vol. 3, A.H. Keane, (trans.) (London: Chapman and Hall, 1892), p. 516. A coalition of local Bari-speakers were joined by other Bari-speakers to the north and west, including Nyangwara, Mandari, Aliab Jieng and attacked Lado, Junker reported, laying siege to the station and cutting it off from Rejaf.[2]Junker, vol. 3. (1892), p. 516. The attack on Bor was led by the prophet Donlutj (Gray, A history of the Southern Sudan 1839-1889 [1961], p. 161). According to Simon Simonse (private comm.), the … Continue reading Soon after, 5,000 people attacked Rejaf.[3]Junker, vol. 3. (1892), p. 517. “The whole Bari tribe arose and attacked Rejaf,” Fadelmulla Murjan, a bugler in Emin Pasha’s force at the time later recalled, “and it was only by calling up troops of [other garrisons at] Silal, Kiri, Mogi, Lebere, Patiko and Wadelai, that we were able to [repel the attack].”[4] South Sudan National Archive, Juba: EP 10.B.2. Allah Water Cult. E.B. Haddon (1921). The testimony provided by Fadelmulla Murjan (“Fad.” or “Fademula Murjan” in contemporary documents) is at … Continue reading

Emin Pasha attributed the uprising to the pillaging of herds and granaries by Turco-Egyptian forces—the grabbling of land “anyhowly,” in Simon Soro’s phrase—, the encouragement provided by the news of the successes of the attack on the garrison at Rumbek in 1883, the attacks on the garrison at Bor, and the Mahdist rebellion against the Turco-Egyptian regime, and the incitement of Madhist “emissaries.”[5] Emin Pasha, and Schwinfurth (ed). Emin Pasha in central Africa : being a collection of his letters and journals (1888), pp. 490. On the destruction of the garrison at Rumbek in 1883, see Andrew … Continue reading This resistance hastened the local collapse of Turco-Egyptian authority and forced Emin Pasha to withdrawal to Wadelai (in present day Uganda).[6] Simon Simonse suggests the breakdown of Emin’s position in the region was hastened by the blockage of the Nile, which prevented steamers from reaching Lado and left him without the trade goods … Continue reading Mahdist forces occupied Rejaf from 1888 until their defeat by Congolese troops in 1897, when the Belgians took over the Lado Enclave. Throughout these periods, plundering was a major method of acquiring food to support garrisons.

“These are the people of Nyangwara when they were taken to work in construction in Rajaf. They were saying, when they were taken to Loguek, ‘When are we going to return to our village?’” Chief Simon Soro relates a song expressing the Nyangwara laborers’ longing to return home. They had every reason to fear that they might not. The violent dispersals, displacements, and demands for labor experienced by residents of the Lado Enclave seemed to echo the loss and dislocation of the 1860s, only thirty years earlier, when roughly 2,000 slaves had been carried away from the region each year. (“This talks about the Turkish soldiers. The ones who came here to destroy us….”: By the 1860s, the trading road from Lado to the zeriba of Ahmed Atrouche, an ivory hunter and former agent of the slave and ivory trading firm, Agad & Co., passed through Nyangwara territory very near Rokon.)[7] See G. Douin, 1941. Histoire du Règne du Khédive Ismaïl, Vol. III part III (1874-1876), chapter 3, pp. 145-156, which describes Gordon’s 1875 overland route from Lado to Macraka. (available … Continue reading

The burden placed on Equatoria’s residents by the labor demands of Belgian stations, their farms, and the roads supplying and linking them together was enormous. Laborers were needed to build and fortify stations, clear and maintain the roads supplying their lines of communication, and to carry supplies. Troops were regularly sent to round up laborers and empty granaries. Those villages that were judged to be uncooperative were ransacked: their granaries emptied, livestock led away, and their houses burned. Entire villages picked up and moved across the river to escape the Belgian appetite for grain, labor, and carriers.

A song recorded near Rokon by Beaton, for example, relates how, in retaliation for refusing to provide laborers to the Belgians, a Pöjulu chief named Gindalla Lomurö was tied up with ropes and his people scattered, “even to the hill of Logwek.” The chief laments: “Those, whose strength knows no gainsaying, have dispersed us; we are scattered.” [8]A.C. Beaton, Some Bari Songs, Sudan Notes and Records 18, no. 2 (1935), p. 282

Rejaf was a large station comprising barracks of red brick with thatched roofs for two thousand troops all surrounded by dirt ramparts raised by Nyangwara laborers. It was said by Chauncey Hugh Stigand to have acquired its name from the Arabic word رجاف , meaning “tremor,” owing to the frequent earthquakes felt there. [9]C.H. Stigand. Equatoria: The Lado Enclave (1923), p. 87. It is spelled “Regiäf” or “Rageef” by Baker (1861), “Rejaf” by Stanley (1873), “Regaf” by Junker (1875) and Casati (1879), … Continue reading The striking conical hill with a square top nearby had long been called Logwek. Over time, the prominence of the station and the their proximity led many to refer to the landmark as “Rejaf hill.”

“We are very tired, we built these places.” There was in the exhaustion of Juba’s builders a history that made the act of building a house suggestive of the entire political-economy of South Sudan. Town-building was an important means of organizing and administering imperial subjects. It also required much monotonous, grinding labor. Beginning in 1927, former slave soldiers were transferred to Juba from Mongalla, Gondokoro, and Rejaf and officials instituted a system of corvée labor by which area chiefs were forced to provide gangs of laborers each month: “Mundari, Nyangwara, Lokoya, they all came in,” Simon Soro says.

Chapter 2. “In those years, Juba was just a bush…” Chief Simon Soro remembers Juba in the 1940s.

“And the school was not under the government, it was under the Church [CMS]. It was a church and also a school providing education.” During this period, government schools provided only vocational training.[10]SAD.83/1/90, 1957: Kathleen Wood to Alice Davies Missionary schools, in contrast, provided a more academic curriculum. The Church Mission Society (CMS) is a British Anglican missionary society.

Rev. Cuthbert Arthur Lea-Wilson founded the C.M.S. Nugent Memorial intermediate school with funds from a legacy from Sophia Nugent. Also known as the C.M.S. Juba Boys’ High School, it was the first post-elementary school in the South. The school was located on a site beside the present St. James Parish, which lies just northwest of the Juba Stadium. The Nugent Memorial secondary school was transferred to Loka in 1927 and the Juba Training Centre (now the Juba Commercial School) was opened in its place to train clerks, bookkeepers, and junior administrators.

“Archdeacon Shaw and Archdeacon Gibson liked me very much because I was very clever in school.”

Archdeacon Archibald Shaw (1879-1956) was born in Edgbaston near Birmingham. Shaw attended Bromsgrove School before going up to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he took a BA in 1900, before entering Ridley Hall, a theological college at Cambridge. He was ordained as a deacon in 1903 and a priest in 1904. He was briefly curate at Walcot, Bath, in Somerset before being accepted by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in 1905. Shaw was a stubborn man who had difficulty getting along with other missionaries. He and five other young men established a mission site at Malek, a few miles upriver from Bor. By 1908, Shaw was the last missionary at the station; illness, loneliness, and “inter-personal tensions” had led to the departure of his colleagues. Shaw was Secretary of the Church Missionary Society (1907-1936) and Archdeacon of the Southern Sudan (1922-1940). Though his duties led him to travel widely across Southern Sudan, Malek remained his headquarters. Shaw had a talent for languages and published several papers on Jieng stories and songs.[11]Archibald Shaw. “16. A Note on Some Nilotic Languages.” Man 24 (1924): 22–25. SHAW, ARCHIBALD. “DINKA ANIMAL STORIES (BOR DIALECT).” Sudan Notes and Records 2, no. 4 (1919): 255–75. … Continue reading He also remained stubborn, autocratic, and difficult. Shaw was relieved of his position as secretary of the Mission by 1936. When he was relieved of his position as Archdeacon in 1940, Shaw left Malek for Kenya, where he served as an Army Chaplain during the Second World War. He later started a farm at Molo in the Kenya Highlands. He died in Karen, near Nairobi, on August 26, 1956.

Archdeacon Paul O’Bryan Gibson (1890 -1967). Paul O’Bryen Gibson was born at Hawes, Wensleydale, in February 1890. He went to preparatory school in Scarborough, on the English coast, and then to Shrewbury School, where he won a scholarship to Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He entered Emmanuel College in 1908, where he read history. He entered Ridley Hall in 1912. He was ordained in 1913 and took his BA in 1916. He was a missionary in Southern Sudan from 1917 to 1956, serving in Malek, Lau, and Yei, where he started a school. He succeeded Shaw as Archdeacon of the Southern Sudan in 1940. In 1948, Paul was made Secretary of the Church Missionary Society Mission and returned to Juba, where he lived with his wife, Mary, until 1956, when he returned to England. He was rector of Wingfield, Wiltshire, from 1957 to 1962.

“So they took me to be a teacher—there at Bilnyang Mountain, I have been a teacher for 5 years.” Simon Soro is referring to Biliniang Mountain, a peak lying to the west of Liria, roughly 28 kilometers east from the center of Juba. Soro does not specify exactly where he taught; in 1951, if one were to draw an arc from Mongalla, through Liria, and back to the Nile, the half circle would encompass about two primary boys schools, one primary girls’ school, and twelve “bush schools.”

“… the centre where Captain Cook[e] (colonial official) was staying….” Captain Robert “Bob” Chevallier Cooke (1891-1972) was Juba’s District Commissioner (c.1928- 1945) in those days.[12] Not to be confused with Mr. C.L. Cook, the Educational Secretary to the Church Missionary Society during this period.

R.C. Cooke had joined the British Army’s Norfolk Regiment in 1914. In 1917, he was seconded to the Egyptian army and was stationed in Taufikia. He joined the Sudan Political Service in 1928. His first appointment was to Opari-Kajo Kaji. As District Commissioner, his office was in the Equatorial Province headquarters, the “Mudeeria” (or Mudiriyah) which gave the roundabout there its name. Like other British officials, Cooke is usually shouting at someone or ordering them to do something when he appears in oral narratives. Consider Chief Lolik Lado, B-Court Chief of Liria (1934-1988), whose recollection of Cooke was recorded by Simon Simonse: “When I entered his office, Cooke put the chain of the President of the Liria B-Court around my neck before I could say anything. When I tried to protest, he shouted: ‘Nonsense! Shut up! Khartoum has already decided….’ He got up and chased me out….”[13]Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster (Fountain, 2017),, p.152.

Cooke is also remembered for having played against the Malakia Football Club.[14]S Nakao, A History from Below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927, The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 31 (2013), p. 148

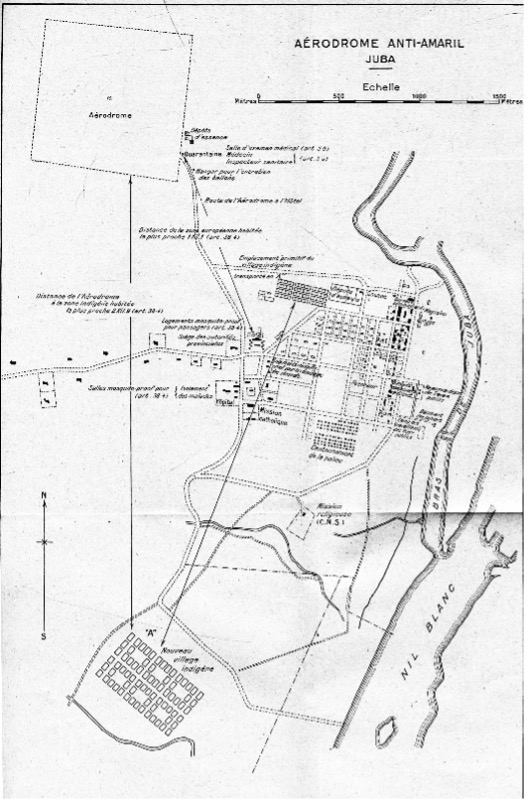

“And then Malakia. This Malakia, they brought it from the airport.” By the early 1930s, about one thousand people had settled at Burusoki, which lay to the southeast of the Juba aerodrome. Some were former slave soldiers, earlier transferred from Mongalla, Gondokoro, and Rejaf; others were laborers provided by surrounding communities to build Juba’s roads and buildings. In 1933 children in Wau, Rumbek, and Juba showed exposure to Yellow Fever, which can lead to severe liver disease and death. In June 1934, a case of Yellow Fever was confirmed at Wau in Bahr-el-Ghazal.[15]Governor-General’s Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1934, p. 79, 126.

As a precaution against the spread of the disease, aircraft were prohibited from flying to other territories from Bahr-el-Ghazal and the Juba and Malakal airports, two stopover stations on the Imperial Airways route between London and Cape Town, were made into “anti-amaryl aerodromes.”

What this meant was that each aerodrome was surrounded by a nearly 3 km residential cordon (for those designated as “natives”) and equipped with a medical officer and mosquito-proof quarters for medical inspections, isolation, and passengers. Burusoki was located within the 3 km cordon. Its residents were abruptly transferred to Burokorongo (today called Malakia) and Burusoki was demolished. Malakia was laid out on a ridge rising from the bank of Khor-bou. It was composed of the Malakia Primary School and seven residential blocks, each of which were divided into ten plots demarcated by castor oil trees.

The forced relocation of Burusoki’s residents and the establishment of a residential cordon for the town’s “native population” helped to entrench Juba’s residential segregation. By the late 1930s, like other colonial towns and cities, Juba’s center comprised a sanitary district (the part of the town with piped water, drains, and the provision for waste removal), where Europeans resided, surrounded by a kind of cordon sanitaire created by the prohibition against “native” residents within about 3 kilometers of the aerodrome.

Further reading: For an excellent wider discussion about how disease control became a crucial part of the expansion of colonial power in Southern Sudan during the early twentieth century, and why it was so often experienced as “punitive and invasive …rather than as a source of healing” (212), see Cherry Leonardi’s Knowing Authority: Colonial governance and local community in Equatoria Province, Sudan, 1900-56 (PhD dissertation, Durham University, 2005), particularly, Chapter 5, “Chapter Five: Knowing the Body: Medicine, Force and Punishment” (pp.207-238).

“And there were a few shops. The traders were Greeks. And the Arabs were few… The white people who did business were all Greeks. And the Arabs were few.” There is a long-standing presence of Greek merchants in the region. At the end of the nineteenth-century, Greek and Syrian merchants made up a substantial portion of a mobile strata of petty traders in the region. These merchants gradually established themselves in colonial stations and towns across South Sudan, eventually building depots and coordinating trade and travel.

“Banayote” probably refers to Panayiotis.[16]George Ghines, private communication, January 2024

“Christo Karsasse,” or Christopher Crassas was a Greek merchant with a store in Juba nearby the wharf. His brother, Anthony Crassas, was the proprietor of Juba’s first cinema, the Juba Picture House.

“[T]hose of Hajjar” probably refers to the family of George Hagger, whose father had migrated to Sudan from Syria and had a retail shop in Juba. George was a prominent figure in Juba. He established coffee and tea businesses in Kajo Kaji and Yei, a cigarette factory in Iwatoka, and warehouse and soap and cigarette factories in Juba. During the 1940s, George was a member of the Municipal Council in Juba.

“…the war of Hitler was intensifying. Hitler was fighting and talking over the radio. And the people were frightened.” During the 1940s, the use of public radios, mobile cinemas, pamphlets, and other media was greatly expanded to manage Sudanese perceptions of the Second World War. British officials worried that events in Europe would diminish them in the eyes of Sudanese.[17] Sikainga, Ahmad Alawad. 2015. “Sudanese Popular Response to World War II.” In Africa and World War II, edited by Judith A. Byfield, Carolyn A. Brown, Timothy Parsons, and Ahmad Alawad Sikainga, … Continue reading Free wireless sets were distributed to social clubs “to add to the effectiveness of B.B.C. Arabic broadcasts,” the Civil Secretary wrote, “and to reach a section of the public who are ill-informed and apt to be misled by foreign propaganda.” [18]South Sudan National Archives (SSNA), Juba: Civil Secretary’s Office, 3 February 1939. UNP/36.F.4. In addition to many private radios in Juba, there were public sets in the Juba Officials’ Club and the P&T Gonio Officials Club. [19]Goniometric (Gonio) stations carred out direction finding against radio traffic and took bearings on hostile aircraft. Radio programming in Englich and Arabic provided news bulletins about the war in between religious texts, poetry, lectures, music, public health talks, and updates about public events. Pamphlets in Arabic and English, with titles like ‘Battle of Britain’ (also in Greek), Churchill Speaks,’ and ‘Facts about the War’ were circulated. [20]SSNA, Juba: Press & Publicity Section, Civil Secretary’s Office, Sudan Government. 1942. Summary of Work During 1941. In addition to radio broadcasts, a steady stream of war photographs, illustrated broadsheets with Arabic titles, pamphlets, colored posters, and mobile cinema newsreels about the war ensured that “the war of Hitler” was a constant topic of conversation.[21]SSNA, Juba: Press & Publicity Section, Civil Secretary’s Office, Sudan Government. 1942. Summary of Work During 1941., p.8

Indeed, the constant stream of war propaganda was so effective, Near and the Middle East reported, that Juba’s “trigger-happy police are said to have regarded most approaching planes as Italian, and succeeded in holing but not harming a Lockheed and a gladiator!”[22]Anon. The Growth of Juba. Great Britain and the East 61 (1945), p. 42

Juba underwent a period of tremendous growth during the 1940s. For an account of the great disruption caused to the town by the labor demands of the Second World War, see To the Juba Wharf.

“People like Omar al Beshir were still young. Ismael al Azhari was a big politician. With Sirr el Khalifa. They took the chiefs… to join them… because the educated people were few.” Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s head of state from 1889 to 2019, was born in 1944 in Hosh Bannaga, a small village beside the Nile about 100 miles north of Khartoum.

Ismail al-Azhari (1900–1969) was the first Prime Minister of an independent Sudan. Born in Omdurman, he attended traditional religious schools until his grandfather, a prominent religious scholar, sent him to Gordon Memorial College, becoming a teacher of mathematics from 1921 to 1927. From 1927 to 1930 he attended the American University in Beirut. He served in the Education Department from 1921 to 1946. Al-Azhari was a co-convener of the Graduates’ General Conference in Omdurman in 1938, where he delivered an introductory speech, and was appointed General Secretary. Early nationalist organizations in Sudan, like the Graduates’ Conference, grew out of social and literary clubs, where graduates from similar professional backgrounds cultivated habits of argument and discussed every subject: the salaries of Sudanese graduates, the Gezira scheme, Sudan’s debt, the unity of the Nile valley, the place of religion in political life, Sudan’s relationships with Egypt and the United Kingdom, competing ideas about how to achieve Sudanese self-determination, and, of course, literature and the day’s events. Al-Azhari had a talent for navigating the divisions created by debates about how to achieve Sudanese self-government, becoming in 1940 (and in 1943-45) President of the Graduates’ Congress, which was founded to overcome graduates’ factionalism. In 1946, he left his post in the Education Department, where he had served since 1921, to pursue politics full-time. From 1944 to 1952, he was President of the Ashiqqa party, “which advocated Sudanese independence under the Egyptian monarchy”; he was President of a party formed by the merger of Ashigga and three smaller parties, the National Unionist Party (NUP), from 1952; and Prime Minister of the Self-Governing Sudan 1954. In 1954, thousands marched in the streets to protest any union with Egypt and it became evident that to unite Sudan and Egypt would risk civil war. In 1955, al-Azhari led the country to independence in 1956. After forming a coalition government with Umma Party rivals, he was forced to resign. Abdallah Khalil of the Umma Party took his place at the head of coalition government.

“But even there, they started quarrelling among themselves. Every time, they made coups… Until Abboud took over. … He made a lot of changes.” The formation of the coalition government under Adallah Khalil did not resolve unresolved questions about Sudan’s place in the world, (the country’s relationships with Egypt and the United Kingdom, economic development and the United States), and South Sudan and regional autonomy within Sudan. In November 1958, General Ibrahim Abboud took control of the country, justifying the military takeover by saying that the military had no choice but to save the country from the chaos of factionalism and misrule. Abboud declared a state of emergency and suspended the constitution, abolished political parties, suspended trade unions, and refused South Sudanese calls for federation.

“It went on like this until the disputes between the Southerners and the Arabs escalated.” Growing political unrest led to the resignation of General Abboud during the October Revolution of 1964. A coalition government was formed and Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa (1919–2006) was appointed Prime Minister of Sudan in 1964. Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa, a graduate of Gordon Memorial College and Oxford, was a civil servant who had earlier served as the Province Education Officer of Equatoria Province, based in Juba (1950-1955), then Chief Inspector (1956), and Assistant Director of Education in Southern Sudan (1957-1960). During his brief tenure as Prime Minster (October 1964 to June 1965), Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa convened what came to be known as the Round Table Conference of 1965, which brought together 24 Southern representatives and 18 Northern party representatives to discuss the unity of Sudan and the federal status for the South.

In the mid-1950s, when the journalist and politician Bona Malwal was the Juba Commercial Secondary School’s basketball captain, he used to play basketball with Sirr al-Khatim and George Hagger (see above).

“It went on and on like that… Until they obtained… their own government.” The Southern Regional Government existed between 1972 and 1983. It was established by the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, which ended the civil war in the southern provinces of Sudan.

“We went and progressed slowly, little by little… But all the finances were still under the Arabs. And it started for the second time [1983]. … They argued for some time and people like John Garang were present until they left.” John Garang de Mabior (1945-2005) was born in June, 1945, in Wangulei, Twic East. Orphaned at ten, he was sent by an uncle to attend primary school in Tonj (1952-1955). After primary school he attended the Bussere Intermediate School in Wau (1956-1959), and then Rumbek Secondary School (1960-1962), where his schooling was interrupted by unrest. After attempting to join Anyanya, he was encouraged to complete his schooling. He resumed high school in Tanzania, winning a scholarship to attend Grinnell College in Iowa, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in economics (1968). The next year, he won a Thomas J. Watson fellowship to study rural development at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He returned to South Sudan and he joined Anyanya in 1970. He was absorbed into the Sudanese army after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement. He took a study leave in 1977-1981, during which time he attended Iowa State University and earned a doctoral degree in agricultural economics in 1981. He defected from the Sudanese army in 1983, joining the rebellion in the South. By the summer of 1983, he was chairman of the SPLM and commander-in-chief of the SPLA.

He led the delegation that negotiated the CPA and became Sudan’s first vice president in 2005. He died in a helicopter crash the same year.

Chapter 3. “My father was a chief… The British used to visit the chiefs in their villages…”

“In those days, the chiefs… like my father…, Captain Cook[e] used to visit them in their homes. ‘Do this,’ [Cooke demanded,] ‘This road you make like this….’ While Simon Soro presents the perspective of a chief, viewers should pay attention to his criticism of corvee labor and other aspects of imperial rule, which is first expressed through the songs sung by Nyangwara laborers and threads through stories of the exhausting labor of building Juba, and the representation of colonial officials. Captain Cooke, the District Commissioner at Juba, for example, always speaks in the imperative: ‘Do this…!’ and demands that others carry his luggage.

In oral traditions, colonial officials are often portrayed as shouting commands, a way of speaking that embodied the logic of the colonial regime, whose archetypal work was road-building, crushing stones, and portage. During this time, the government roads in Equatoria Province were gravel-surfaced and maintained by laborers attached to camps laid out at intervals of six miles.

“That’s how he worked. He didn’t sit at his desk, he used to go and see the place…” Simon Soro here obliquely criticizes NGO workers and government officials of the present day who, he suggests, by not visiting the countryside or checking up on how money is being spent, allow corruption to flourish.

“The lazy people were arrested and given a place by the chief to cultivate…” Viewers surprised by Simon Soro expressions of nostalgia for the power held by chiefs under the Anglo-Egyptian colonial regime should recall that Simon Soro is a chief. Additionally, as the historian Cherry Leonardi has written, “the nostalgia for more effective chiefly authority reflects a widespread desire for regularized, consistent mechanisms for preventing conflict and enforcing justice.”[23]Cherry Leonardi, Making Order Out of Disorder: Customary authority in South Sudan (RVI, 2019), p.20. https://riftvalley.net/publication/making-order-out-disorder-customary-authority-south-sudan/

During the early years of the Anglo-Egyptian regime, officials periodically rounded people up, arrested them, and put them to work clearing the river of vegetation or clearing roads, justifying their actions reference to laziness, and claiming that they were unable to find anyone willing to work for wages.

In Juba, as the town’s population grew with the arrival of petty traders, domestic workers and other casual laborers, residents’ family members, and various guests and other visitors, officials worried that this population growth would loosen customary bonds of authority and breed idleness, diverting hands from agricultural work. So, each April, at the start of the rains, officers made their way through Juba, arresting people, loading them into government lorries, and ‘despach[ing] them … to their home centres’ to begin farming.’[24]L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), 7.

Chapter 4. “I went to Khartoum, and I saw the house of the Mahdi…” Chief Simon Soro recalls visiting the Khalifa House Museum, established in Omdurman in 1928 to preserve the history of the Mahdist State (1885-1898).

“They took us, the chiefs, to Khartoum… They brought us to see the house of the Mahdi.”

There is a long tradition of Egyptian, British, and Sudanese regimes bringing chiefs from South Sudan to the north, to see Khartoum. In 1874, Baker had sent Laku-lo-Rundyang (Abu-Kuka) to Khartoum to impress him. British officials drew on this tradition during the 1920s and 1930s, when they arranged sightseeing tours that were designed to discourage anti-government activities among South Sudanese chiefs. During the lead up to Sudanese independence in the 1950s, chiefs were taken to Khartoum for a crash course in government.

The conquest of Sudan was not only a matter of the dispossession of indigenous lands or the installation of an imperial regime. It was also a matter of colonizing history. In the early nineteenth-century, British officials were keen to interrupt the transformation of memories of Mahdist self-determination and resistance into Sudanese heritage. To counter “the patrimonialization of the Mahdiyya,” (in the historian Iris Seri-Hersch’s phrase), British officials established museums to provide “counter models” of Sudanese patrimony, which served to delegitimize memories of the past.[25]Iris Seri-Hersch, 2001, “Nationalisme, impérialisme et pratiques patrimoniales : le cas de la Mahdiyya dans le Soudan post-mahdiste,” Egypt/Arab World (Heritage Practices in Egypt and … Continue reading

The Khalifa’s House Museum was one of these counter models; it was meant to portray the Mahdiyya (1881-1898) as a period of nonstop violence, atrocities, and tyranny. It comprises many rooms with low ceilings with a collection of old weapons.[26]In A Line in the River (Bloomsbury, 2018), Jamal Mahjoub describes a visit there in his childhood. The museum is located opposite the Mahdi’s tomb in Omdurman in the house of Abdullahi ibn-Muhammad al-Khalifa, or “the Khalifa,” the successor of Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, who led a successful revolt against the Ottoman-Egyptian regime in Sudan in 1881, established the Mahdiyya state, and died in 1885. South Sudanese visitors did not necessarily come away from their visit with exactly the message intended by British officials.

Chapter 5. “How will we tell our history if old names are erased?”

Crucial to telling South Sudan’s history is identifying the various locations through which the story unfolds. Bureng Nyombe’s “Some Aspects of Bari history” (2007) begins with the movement of Bari people from the north. Severino Ga’le’s “Shaping a Free Southern Sudan” (2002) describes Madi migrations and the movement of his own family. The history of a place, for many people, is foremost a story about how an ancestor founded it: where they came from, why they left, how they arrived in the place their descendants now live, gather people around them, and so forth. Stories like these encode local knowledge and anchor claims to land. These claims take on special meaning in a region where, it is important to emphasize, empire, conflict, land grabbing, and natural hazards have made it very difficult for people to create enduring ties to places. People look to these histories for a sense of rootedness and the renaming of places has come to embody ways in which territory has been “grabbed anyhowly.”

The station at Lado was established in 1874 by Charles Gordon, the Governor of Equatoria then, when the Nile at Gondokoro silted up and made the station inaccessible to steamers. It was named after Lado-lo-Möri, the Bari chief who controlled the region in those days. Though for several year authors commonly wrote “Jebel Ladó (Nyerkáni),” with the older name in parentheses, the station’s name came to overshadow “Nyerkenyi” in travelers accounts and maps produced by outsiders.

The names of other nearby mountains, Loguek, Körök (“Kerek” in contemporary documents), and Kanufi, were replaced by the non-local residents of growing stations and towns: Loguek came to be called Jebel Rejaf; Körök, Jebel Kujur; and Kanufi, Jebel Luri. The maps on which these names appeared also furthered imperial ambitions. They provided documentary evidence of imperial possessions and provided practical information for navigation and reduced the newcomers’ reliance on residents there. But place names were not just recorded by surveyors and written on maps by cartographers. They were also spoken and debated. South Sudanese created new names by quoting past speech to memorialize painful memories.

“When the British left. The Arabs came here. They created different places… Atlabara… Rujal Mafi… And the indigenous were present – As they were saying, “Rajali mafi” (“No men”). Where did the men go?”

Simon Soro’s examples of place names are ones that evoke displacement, dislocation, violence, and resistance. For example, Atlabara is the name of a neighborhood which lies south of the University of Juba and comprises part of the old “Native Lodging Area.” Several competing folk etymologies for this name are current in Juba, but all share a few basic features. The phrase “atla’a barra” is rude. It’s a command meaning “get out!,” if the speaker and listener are inside a shared space, or “come out!,” if one is speaking from outside. It is the sort of thing that a soldier would shout at someone from whom they expect “submission and respect.”[27]Deng Awur Wenyin, “Immoral Naming of Some Residential Areas in Juba,” Second International Sudan Studies Conference Papers: Sudan: Environment and people, 8-11 April (1992), p.130.

The anthropologist Christian Doll spoke to residents of the area who suggested that the name might memorialize events of 1947, when in the early days of Sudanization in anticipation of the independence of Sudan, soldiers from the north went around tossing residents out of their houses, telling them to “get out!” Deng Awur Wenyin, Professor of Law at the University of Juba, suggested that the name may derive from the expansion of Juba in the 1950s, when residents of undeveloped plots were made into squatters by surveyors and then evicted by police, shouting, “Atla’a barra!”[28]Deng Awur Wenyin, “Immoral Naming of Some Residential Areas in Juba,” Second International Sudan Studies Conference Papers: Sudan: Environment and people, 8-11 April (1992), p.130. Other versions draw on the meaning “come out!” Michael Lado Allah-Jabu, Juba’s mayor from 2001 to 2023, for example, attributed the name to 1965, during unrest in Juba, when northern government soldiers patrolled the neighborhood and went house-to-house, shouting “come out” in their search for men that they assumed were rebels or sympathetic to their cause.[29]Emmanuel Akile, Juba Mayor explains why Rujal-Mafi, Libas-Mafi, Atlabara be renamed. Eye Radio, April 21, 2022. (avalable online, … Continue reading Another neighborhood, Rejel Mafi “no men [here],” Doll writes, “was named for efforts to resist these patrols, when men who deserted the area before the nighttime raids. “When the northern soldiers arrived and shouted ‘atlabara’,” Doll writes, “the women replied ‘rejel mafi’, or ‘no men’.” This “[b]oth Atlabara and Rejel Mafi have retained these names until today, allowing a past moment of state violence—and an act of quiet resistance—to continue to mark, and be memorialized within, the city.“[30]Christian Doll. 2023. HOW THÖŊ PINY BECAME JUBA NA BARI: Naming and Place-Making in Urban South Sudan. Ijurr (available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-2427.13214).

Chapter 6. “Juba came from the name of a person.”

Place names confer rights and standing. Many have genealogical meaning. Simon Soro describes how the names of prominent people were appropriated by colonial officials and applied to government stations. As these names were extended first to the area where the station was located, which generally had a pre-existing name, and then to cover districts, their geographic reference came to overshadow the memory of those after whom they had been named. As a result, Soro says, “the owners of the place were completely knocked out, as if it’s not their place.”

“Here, the founder of this place is called Jubek.” Various stories account for the origin of the name “Juba.” The most common is that the town is named for a chief named Jubek, who together with his people was made to vacate the location where Juba was subsequently built. The political scientist, Naseem Badiey, who carried out research in Juba in 2006 and 2008, recorded a version of these events given by Tongung Lado Rombe, a Bari elder and Community Association Chairman: “[Juba] was built on the site of a Bari village called Tindu… and gained its name from the village chief who was called Jubé [or Jubek].”[31]Naseem Badiey, The State of Post-conflict Reconstruction (James Currey, 2014), p.38.

Further reading: Jubek’s Grave, Juba in the Making.

“Kajo-Keji… That’s the name of someone.” The station at Kajo Kaji was named for a prominent chief, Lishaju, whose nickname was Kajok Köji, a phrase that has been variously translated to mean “a lot of cattle” or “calves in the kraal.” Lishaju’s father, a rain-maker, established villages there. In Stigland’s telling, Lishaju was an old chief who asserted his authority through a somewhat retiring posture. He seemed to “take… no active part in anything,” Stigland wrote, and “a stranger might be many months or even years in the country without discovering that he is practically the paramount chief of the Kuku.”[32]Chauncy Hugh Stigand, Equatoria: The Lado Enclave (Constable & Co., 1923), pp. 70. He did not ordinarily involve himself in deciding cases. But it was through this mild bearing that Lishaju embodied the moral unity of the community as a whole. Indeed, Stigland said, “no important decision is ever given without first referring to him, and he is the final arbitrator in all matters and disputes which cannot be settled by the other chiefs.” [33]Stigland, (1923), pp. 70.

Lishaju had many cattle and several sons. His son Enki became chief of Kajo Keji station after his father. (Enki was replaced by his brother, Yonguli, when Enki was “deposed for misbehaviour.”) Lishaju’s son Tete, known as lo Dyanga, after his mother, Dyanga, later became a popular Paramount chief.[34]Kuyok Abol Kuyok, South Sudan: The Notable firsts (Authorhouse, 2015). Tete Kajok Koji (c. 1888-1968). Like other prominent men, Lishaju accumulated names. By the early 1920s, his garbled and misspelled nickname had been extended from the station to cover an entire district in Mongalla Province, Kajo Kaji. “To avoid the confusion” caused by all this, Steven Wöndu writes, “the chief bought himself the name Wösuloba [, meaning ‘he eats for free,] from a friend to the east.”[35]Steven Wöndu, From Bush to Bush (Nairobi, 2011), p. 1.

“Yambio is the name of someone.” Prince Gbudwe Bazingbi (c.1830 – 1905) was named Yambio at his birth. He grew up in the court of his father, Bazingbi Yakpati. He was his father’s fourth son. He was also his father’s favorite. He led campaigns, taking the name Gbudwe (meaning, ‘to organize or settle’ or govern or conquer) after a victory that was important to him, and united the region’s independent kingdoms to create an empire. His domain stretched from Mopoi in the west almost to Maridi in the east, encompassing much of what was Western Equatoria. He ruled from 1868 to 1905, when he was undone by his steadfast refusal to submit to imperial conquest and killed by a British patrol.

Further reading: The anthropologist Zoe Cormack, whose research has focused on art, material culture, and the history of collecting in South Sudan, has written about “The Political Life of King Gbudwe’s Grave” for the Rift Valley Institute.

“Nearby here from Sultan Jambo… That’s a person. You see?” Jambo Lowoh (c. 1889-1976) was born around 1889 in a Beriba village near to the town that today bears his name. He was a gendarmerie for the Belgian regime in the Lado Enclave until it reverted to the British, when he joined the Anglo-Egyptian police force in Amadi. He succeeded to the chieftainship in 1929 and rose through the ranks of the chiefs’ court system, eventually becoming president of the Amadi B court. He was dismissed as president by the British DC in 1952 after a miscalculated alliance with Salah Salim, an Egyptian Government Minister, provided Jambo’s rival, Chief Timon Biro, with an opportunity to lead a call for his removal.

Durham has a photo of him. [PHOTO: SAD.775/11/87 (Thomas Halliday Baskerville Mynors collection)]

Chapter 7. “I’ve never held a gun in my life…”

What anchors claims to a place? There are stories that imagine South Sudan’s wars as a long-fought path to autonomy. Other stories are less certain. Simon Soro describes how his two sons each kept their dignity when they were killed: one was executed for refusing to fight, the other killed while saving a child.

“Since the Anya-Nya rebellion, I have never been to the bush.” During the 1950s, some Southerners saw the increasing numbers of northern Sudanese administrators and traders as a kind of internal colonization, merely replacing the British. Tensions in the South grew as Sudanization led to the replacement of British administrators in southern districts almost entirely by Northern Sudanese. These tensions culminated in violence in Juba, Yei, Yambio, Nzara, Malakal, and Wau during the summer of 1955. The Torit Munity of that year was a prominent episode in that larger quarrel about the direction of Sudanese independence. The next seven years (1956-62) saw an escalation of conflict driven in large part by heavy-handed policing that multiplied southerners’ grievances and drove many into insurgency.

The historian Øystein Rolandsen has argued that this rebellion was the outcome of needless and brutal panic among administrators. By 1963, this violence culminated in civil war. The Anya-Nya rebellion came to be called after the insurgents, called Anyanya, or “snake venom,” a name chosen to evoke their determination to resist.

“During the time of the SPLA rebellion, they were shelling Juba… Another son of mine… He was the bodyguard of Henry Minga.” The SPLA rebellion is conventionally dated to May 16, 1983, when ex-Anyanya soldiers in Bor refused orders to be transferred to the north.

By 1986, SPLA forces had put Juba under siege. The town become a key government-controlled garrison circled all around by rebel-held territory. During the 1990s, the SPLA periodically shelled Juba.

Henry Minga was a wildlife officer then. He later became Deputy Director for Administration, Regional Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism.

Chapter 8. “People used to live together without fighting…”

“So now people are put in groups. Nuer, Dinka, Nyangwara, Mundari… How did this come about?” People in South Sudan belong to multiple “groups,” many to several groups simultaneously. Any given person might, in certain circumstances, reckon their belonging to a particular group in terms of ancestry or intermarriage, or in relation to set of cultural or livelihood practices, membership in an age-set, schooling, occupation, residence in a town or rural area, or with reference to a particular religious tradition or language. Groups of people in the region have long expanded through the incorporation of smaller groups, the adoption of individuals, and intermarriage. People across the region spoke different languages but still intermarried and solved the problem of belonging to different language groups by learning multiple languages. Marital residence being somewhat flexible, many people have options about where to live, what other families they could belong to, or other communities where they might be able to settle. Indeed, historians like Douglas Johnson and Cherry Leonardi have argued that one way to understand the history of government in South Sudan is as a series of attempts to limit people’s choices about what group to belong to, where to live, and what language to speak.

The term “tribe” refers to a particular administrative structure in South Sudan, which is historically related to the principle of devolution in “native administration.” This institution was based on the idea that people naturally came in bounded units which could be kept separate from each other. As the British administration established itself in South Sudan, it duly began dividing the populace up into a series of administrative units called “tribes.”

Chapter 9. “Before the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, we were all living together in Juba…”

“People were talking in Juba Arabic.” During the 1820s, the Turco-Egyptian state began to push the frontier of its authority, together with slave-raiding and the ivory trade farther south. This trade was extended up the Bahr el Ghazal and White Nile after 1840; and by the 1860s, intermediaries with a talent for translation began to learn the Arabic of the traders. These translators brought the violence of the slave trade under some measure of control by entering into alliances with the slavers, who depended upon them to negotiate local trade. This military pidgin came to be known as “Bimbashi Arabic” (after bimbasi, an Ottoman term meaning “officer”). The dislocations associated with the slave trade furthered the spread of this variety of Arabi, which was increasingly spoken around military garrisons and in urbanizing administrative centers. After 1900, retired slave soldiers and returnees from the north settled in administrative centers in southern towns, forming Malakiya communities where a South Sudanese Arabic was spoken as a first language. The language came to function widely as an intermediary language in courts and markets (hence, “Konyo-konyo Arabic”) across the south, where it was spoken by police, soldiers, clerks, interpreters, and chiefs.

Further reading: Leonardi, C. (2013). South Sudanese Arabic and the negotiation of the local state, c. 1840-2011. Journal of African History, 54(3), 351-372.

Chapter 10. “Education should be the number one priority…”

“A woman is born as a means of communication. She will make you known in other places. Now my daughters are married to Nuer people. People criticized me for that. Now my daughters have all completed university, they are working. Now my name is known over there. What is wrong with that?” Exogamy among Bari patrilineal clans creates networks of alliances that spread a family’s reputation far and wide. These alliances can also be useful in emergencies. Opening multiple channels of information and exchange across long distances through marriage helps to ensure that one can always call on in-laws for help; it keeps options open about where to live and what community to belong to.

Brendan Tuttle

References

| ↑1 | Wilhelm Junker, Travels in Africa during the years 1882-1886, vol. 3, A.H. Keane, (trans.) (London: Chapman and Hall, 1892), p. 516. |

| ↑2 | Junker, vol. 3. (1892), p. 516. The attack on Bor was led by the prophet Donlutj (Gray, A history of the Southern Sudan 1839-1889 [1961], p. 161). According to Simon Simonse (private comm.), the attack on Lado was led by Deng Tonj, a prophet, who was killed in the battle. Bepo-lo-Nyiggilo also played a prominent role in the 1885 attack on the garrisons at Lado and Rejaf. “Yazbashi.” Tribes on the Upper Nile: The Bari. Journal of the African Society, vol. IV., no 13 (October 1904), p.227. |

| ↑3 | Junker, vol. 3. (1892), p. 517. |

| ↑4 | South Sudan National Archive, Juba: EP 10.B.2. Allah Water Cult. E.B. Haddon (1921). The testimony provided by Fadelmulla Murjan (“Fad.” or “Fademula Murjan” in contemporary documents) is at the center of a small literature on the “The Yakan or Allah Water Cult” (Driberg 1931; Middleton, 1963; Leopold, 2005) “Allah water” was a kind of protection medicine, (which was said to prevent death by disease, resurrect dead cattle and ancestors, provide protection against flouting government orders, refusing to pay taxes, and bullets from government guns), that paranoid officials in Uganda in 1919 thought to be responsible for unrest in Arua in 1919 (Mark Leopold, Inside West Nile (James Currey, 2005)). While the evidence does not seem to support Driberg’s interpretation of events in Arua, the song sung by Simon Soro, with its anti-imperial spirit, female character, Keji Lo Lomerot (Keji or Käji, daughter of Lomerot), who recalls Kiden, a Bari prophetess (Simon Simonse, per. comm.) And see Simonse’s Kings of Disaster (Fountain, 2017), pp. 114-115); the imagery of termites has suggestive parallels with the protection medicine described by Fademula Murjan. |

| ↑5 | Emin Pasha, and Schwinfurth (ed). Emin Pasha in central Africa : being a collection of his letters and journals (1888), pp. 490. On the destruction of the garrison at Rumbek in 1883, see Andrew Mawson, The Triumph of Life: Political Dispute and Religious Ceremonial Among the Agar Dinka of the Southern Sudan (1989), p.75; Douglas Johnson, “Deng Laka and Mut Roal: Fixing the Date of an Unknown Battle,” History in Africa 20 (1993), p. 121. |

| ↑6 | Simon Simonse suggests the breakdown of Emin’s position in the region was hastened by the blockage of the Nile, which prevented steamers from reaching Lado and left him without the trade goods needed to maintain networks of patronage through “cargo chiefs.” Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster (Fountain, 2017), p.109. |

| ↑7 | See G. Douin, 1941. Histoire du Règne du Khédive Ismaïl, Vol. III part III (1874-1876), chapter 3, pp. 145-156, which describes Gordon’s 1875 overland route from Lado to Macraka. (available online, https://digitalt.uib.no/handle/1956.2/2889). |

| ↑8 | A.C. Beaton, Some Bari Songs, Sudan Notes and Records 18, no. 2 (1935), p. 282 |

| ↑9 | C.H. Stigand. Equatoria: The Lado Enclave (1923), p. 87. It is spelled “Regiäf” or “Rageef” by Baker (1861), “Rejaf” by Stanley (1873), “Regaf” by Junker (1875) and Casati (1879), and “Reggaf” by Slatin (1879). “Rigaf” by Lieut. C.M. Watson. |

| ↑10 | SAD.83/1/90, 1957: Kathleen Wood to Alice Davies |

| ↑11 | Archibald Shaw. “16. A Note on Some Nilotic Languages.” Man 24 (1924): 22–25. SHAW, ARCHIBALD. “DINKA ANIMAL STORIES (BOR DIALECT).” Sudan Notes and Records 2, no. 4 (1919): 255–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41715806. https://doi.org/10.2307/2788090. Shaw, Archibald. “34. Jieng (Dinka) Songs.” Man 17 (1917): 46–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2788753. |

| ↑12 | Not to be confused with Mr. C.L. Cook, the Educational Secretary to the Church Missionary Society during this period. |

| ↑13 | Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster (Fountain, 2017),, p.152. |

| ↑14 | S Nakao, A History from Below: Malakia in Juba, South Sudan, c. 1927, The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 31 (2013), p. 148 |

| ↑15 | Governor-General’s Reports on the finances, administration and condition of the Sudan in 1934, p. 79, 126. |

| ↑16 | George Ghines, private communication, January 2024 |

| ↑17 | Sikainga, Ahmad Alawad. 2015. “Sudanese Popular Response to World War II.” In Africa and World War II, edited by Judith A. Byfield, Carolyn A. Brown, Timothy Parsons, and Ahmad Alawad Sikainga, 462-479. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑18 | South Sudan National Archives (SSNA), Juba: Civil Secretary’s Office, 3 February 1939. UNP/36.F.4. |

| ↑19 | Goniometric (Gonio) stations carred out direction finding against radio traffic and took bearings on hostile aircraft. |

| ↑20 | SSNA, Juba: Press & Publicity Section, Civil Secretary’s Office, Sudan Government. 1942. Summary of Work During 1941. |

| ↑21 | SSNA, Juba: Press & Publicity Section, Civil Secretary’s Office, Sudan Government. 1942. Summary of Work During 1941., p.8 |

| ↑22 | Anon. The Growth of Juba. Great Britain and the East 61 (1945), p. 42 |

| ↑23 | Cherry Leonardi, Making Order Out of Disorder: Customary authority in South Sudan (RVI, 2019), p.20. https://riftvalley.net/publication/making-order-out-disorder-customary-authority-south-sudan/ |

| ↑24 | L.R. Mills, The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan (University of Juba, 1981), 7. |

| ↑25 | Iris Seri-Hersch, 2001, “Nationalisme, impérialisme et pratiques patrimoniales : le cas de la Mahdiyya dans le Soudan post-mahdiste,” Egypt/Arab World (Heritage Practices in Egypt and Sudan), p. 329-354, https://doi.org/10.4000/ema.2906 |

| ↑26 | In A Line in the River (Bloomsbury, 2018), Jamal Mahjoub describes a visit there in his childhood. |

| ↑27, ↑28 | Deng Awur Wenyin, “Immoral Naming of Some Residential Areas in Juba,” Second International Sudan Studies Conference Papers: Sudan: Environment and people, 8-11 April (1992), p.130. |

| ↑29 | Emmanuel Akile, Juba Mayor explains why Rujal-Mafi, Libas-Mafi, Atlabara be renamed. Eye Radio, April 21, 2022. (avalable online, https://www.eyeradio.org/juba-mayor-explains-why-rujal-mafi-libas-mafi-atlabara-be-renamed) |

| ↑30 | Christian Doll. 2023. HOW THÖŊ PINY BECAME JUBA NA BARI: Naming and Place-Making in Urban South Sudan. Ijurr (available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-2427.13214). |

| ↑31 | Naseem Badiey, The State of Post-conflict Reconstruction (James Currey, 2014), p.38. |

| ↑32 | Chauncy Hugh Stigand, Equatoria: The Lado Enclave (Constable & Co., 1923), pp. 70. |

| ↑33 | Stigland, (1923), pp. 70. |

| ↑34 | Kuyok Abol Kuyok, South Sudan: The Notable firsts (Authorhouse, 2015). Tete Kajok Koji (c. 1888-1968). |

| ↑35 | Steven Wöndu, From Bush to Bush (Nairobi, 2011), p. 1. |

Custom Bus Park,

Freedom Bridge,

Garang Mausoleum,

gumbo-sherikat,

gurei,

Hai cinema,

Hai Gabat,

Hai Malakal,

Hai Malakia,

Hai Neem,

jebel kudjur,

Juba International Airport,

Juba Nile Bridge,

Juba Stadium,

Juba town,

Juba Town Hai Jallaba Mosque,

Jubek's Grave,

kator,

konyo konyo market,

Lagoon Dumpsite,

Munuki,

nyakuron cultural centre,

Souksita,

un house-poc site,

University of Juba