A Night At The Movies

Some of the following is excerpted from « Cinema, Southern Sudan, and the End of Empire, 1943-1965, » by Brendan Tuttle and Joseph Chol Duot, which appears in Sudan, 1504-2019: From Social History to Politics from Below (2022), edited by Mahassin Abd al-Jaliil, Iris Seri-Hersch, Anael Poussier, Lucie Revilla, Elena Vezzadini and published by De Gruyter.

Cover image: « Out for a dance in Juba » by Vonda Adorno (1975). Copyright.

Mobile cinema and making audiences in South Sudan

The first cinema show in Sudan was organized under the direction of Herbert Kitchener in January 1912 to mark the opening of a new section of railway in El Obeid.[1]Lord Kitchener, Consul-General in Egypt at the time, had come to Sudan to greet the King and Queen. A few days before, notables ‘from all parts of the county’ had attended the arrival of the H.M.S. Medina at Port Sudan and the reception of King George V and Queen Mary of England (Fortescue 1912:19). A cinema film was made of the event and shown in El Obeid a few days later. Thousands of people were gathered on a parade ground near El Obeid, Steward Symes, Assistant-Director of Intelligence at Khartoum, wrote, describing how a ‘silence fell on the crowd as a dark object moved across the patch of light,’ and then built into ‘loud gusts of applause and laughter’ with the recognition of familiar individuals among those pictured in film of the arrival of the H.M.S. Medina, the reception of the king and queen, and the presentation of Sudanese notables (Symes 1946:20).

A decade later, in the 1920s, merchants began setting up commercial cinemas in Sudan. The first were small ‘make-shift open-air’ travelling outfits consisting of little more than a few chairs arranged before a bedsheet or a blank wall upon which silent Charlie Chaplin comedies were projected (Ibrahim 1999:38). Larger open-air commercial establishments were set up in the 1930s.

During the 1940s, the government greatly expanded the use of mobile cinema in order to manage perceptions of the Second World War. British officials worried about how Sudanese, like other colonial subjects in similar situations elsewhere, would interpret events in Europe (Sikainga 2015). English- and Arabic-language press conferences were held and radio broadcasts, newspapers, and magazines were put into circulation. Communal listening sets were installed in public places in towns across Sudan to reach more listeners; and special broadcasts in Shilluk and other languages were also established. A travelling cinema was also organized to exhibit propaganda films around the country. ‘The information office directed a steady and ever-increasing flow of hand-outs, maps, photographs, blocks, articles, pamphlets, reviews of the war, calendars, and other publications’, the Governor General wrote of the output of the early years of the war.[2]Governor-General of the Sudan. “Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1942-44 (inclusive).” 126.

This ever-increasing flow of imperial war propaganda and other material carried stories of partnership and unity that portrayed the wartime empire pulling together across differences of class, nationality, and race in a global fight against fascism. Desert Victory (1943), a film about the ‘rout of Rommel,’ and Partners in Victory, a specially commissioned film about the Sudan Defense Force in North Africa, were shown to huge audiences in provincial capitals across all parts of Sudan (Swanzy 1947:71).

But the disturbing irony of this message of unity was particularly apparent to audiences in places like Juba, where the city’s rapid growth was evidence that the Second World War was maintained by the labor, materials, and economic resources extracted by imperial violence. The African Forces Line of Communication (AFLOC)—by which Juba linked up the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States to campaigns fought in the deserts of North Africa—was made possible by the British possession of territory in Sudan and the colonial control of the global movement of people and materials. The roads that carried war materials through southern Sudan were built by forced labor.

The same roads also carried popular entertainments. By 1947, three Government mobile cinema vans were on the road. Their audiences were rural, but by no means small or isolated. 5,000 people attended mobile cinema exhibitions in the Khartoum area in 1947 and more than 230,000 men, women, and children attended mobile cinema shows in rural areas.[3]Governor-General of the Sudan. “Report on the Administration, Finances and Conditions of the Sudan in 1947.” 144. For a comparison of numbers reached by mass literacy campaigns, see Seri-Hersch … Continue reading Over the next years, the movement of mobile cinema vans across the country created mass rural audiences. There was even a cinema train, the Sudan Railways’ ‘Public Enlightenment’ Car, which was equipped with a silent movie projector and portable generator to help reach railroad workers and residents of villages and towns near railways with war films, government information shorts, and educational pictures.[4]US Department of Commerce, 1944. “Sudan Railway’s ‘Public Enlightenment’ Car.” Foreign Commerce Weekly 14, no. 1 (January 1, 1944), 24.

In Juba, mobile cinema exhibitions were announced by loudspeakers attached to the roof of a Landcruiser that drove around town. These exhibitions were held in the open, often following a short lecture or speech that began at sunset. Spectators gathered in front of a white sheet upon which a program was projected which consisted of short films, ranging in length from five minutes to thirty or more, including newsreels showing happenings in Sudan and other parts of the world, American comedies and westerns, short documentaries made by the mobile Sudanese film-making unit for a Sudanese public, and a variety of films made in India, Kenya, and Britain. Films concerning topics of public health or daily life in England were alternated with Cowboy films, Charlie Chaplain features, and Sudan Film Unit productions such as Sudan Independence (1956) or sponsored trade films like King Cotton (1949). Images of dances in distant villages in Sudan and in India (Kathakali, B/W, 8 minutes), developments around Khartoum (Abu Akar, B/W, 10 minutes; Three Towns, B/W, 8 minutes), and public transportation and tourist sites in England (Sudanese in London, B/W, 5 minutes), for instance, prompted reflection on the circumstances of Southern Sudan, the region’s place in the British Empire, and the lives of other colonized people.[5]Public Relations Office, Catalogue of 16mm. Films (February 1952).

The first purpose-build cinema in what is today South Sudan, the Juba Picture House, opened in 1954. Mobile cinema exhibitions had already created large film-going audiences in southern Sudan. When the Juba Picture House opened on the borderlands between the hospital and Juba’s Native Lodging Area, it attracted all segments of Juba society: families, lovers, intellectuals, entertainment seekers, young people, children, and ticket touters and hawkers of every kind. Hai Cinema exists today because for two decades the Picture House gathered all of Juba around itself.

Juba Picture House

During the early summer of 2017, the attorney Joseph Chol Duot circulated a questionnaire survey about cinema-going among some of the men who spent their off-hours around the tea stalls of Hai Cinema. This work resulted in “A Research Report on Leisure Activities, Films, Fashions, and Popular culture in Hai Cinema, now Emmanuel Diocese, Juba (1962-2017),” a study providing a summary of some of the films that people had seen at the Juba Picture House, their recollections of the cost of admission, what people had worn when they went there, where they had sat, and other details. Over the next few months, we spoke with a few dozen people whom Chol had identified as movie-goers in the 1960s and 1970s.

That the Juba Picture House had a history worthy of being told was taken for granted by everyone we talked to. After all, it was the place where the Liberal Party meeting of 1954 was held, when (by Alexis Mbali Yangu’s 1966 account) ‘20,000 persons from every walk of life and from all parts of the South—chiefs, notables, officials, and all other classes of the Southern populace’ (1966:23)—came together in Juba to come to an agreement on ‘the political future of the Sudan’ (Lwoki & Morgan 1954:118). ‘The House,’ as participants called it, held 400 people. Attendees shuttled back and forth between discussions in the House and discussions among all those ‘from every walk of life’ who had come to Juba for the event. The meeting not only produced a statement on federalism; it also provided a concrete experience of the principles and organization of a pan-Southern political association. Liberal Party members, Southern National Unionist Party members, chiefs from Upper Nile, Equatoria, and Bahr El Ghazal, representatives of South Sudanese residents in Khartoum, and ‘Northern Sudanese who claim African descent’ all came together for a slow and thoughtful multilingual debate carried out ‘well and in Good Spirit,’ with their words ‘translated into various languages in the South’: Bari, Zande, Latuka, Dinka, and Arabic (Lwoki & Morgan 1954:121).

*

The Juba Picture House—or Kirrissasa Cinema, as many called it after the cinema’s proprietor Antony Crassas, a Greek businessman, or simply ‘the cinema,’ since it was the only one—was a large motion-picture theatre. At 7pm, when the dim headlights of Anthony’s little light-green Volkswagen swung into view in the distance, the box office would open. ‘And when we saw the car is coming [we’d cry], “oh, Anton. Anton. Anton,”’ one movie-goer recalled. ‘And clap. And people will just rush to the line and be ready to get their tickets.’[6]One person that we spoke to said the car was a Peugeot. Tickets cost three and a half, seven, or fourteen piasters, depending on the seat. For this sum a customer saw movie trailers and one feature film. For a few days during Christmastime Anton put on two showings, with a first run at 7pm and another at 10pm. Many cinema-goers also bought a handful of roast peanuts or a fava-bean sandwich, which could be had for one piaster.

Inside the theatre the town’s social divisions and hierarchies were visible in miniature. Visitors who paid 14 piasters to sit in the first-class class balcony overlooked families, petty traders, and schoolchildren with their mothers—who had paid 7 piasters for second-class seats in the middle of the hall—and ‘the youth’ who had paid 5 piasters to sit in the third-class area. ‘Those in first class were more civilized,’ one cinema-goer recalled, laughing. The third-class section could be rowdy. If any tickets were left over, children could pay 3 ½ piasters for entrance, which got them a place in the already crowded third-class section, where they could sit with their noses practically pressed against the screen. (The Picture House’s latrine offered another entrance through the wooden seat set over a large bucket, which was collected by night-soil men. By lifting the iron flap at the back of the box, pushing the heavy bucket aside, and climbing up, small boys were able to enter the cinema compound without paying the entrance fee.) The town’s teachers, civil servants, and business people, Greeks, Turks, Indians, and Egyptians tended to sit in the first-class seats.

The Juba Picture House opened during a period of great transformation in Juba. The war of 1939-45 had relied on the labor of South Sudanese for building and maintaining roads and bridges, loading cargo, producing food, cutting timber, and soldiering in the Equatorial Corps and East African units. Chiefs were made to impress thousands of laborers to clear and gravel roads and to build bridges for heavy trucks. Officials rounded up and arrested hundreds of ‘able-bodied men’ in order to put them to work. Juba town alone required almost 1,500 conscript laborers to manage 1,000 tons per day of cargo and 800 vehicles each month during the war. All this forced labor produced lasting demographic changes in Juba. Between 1939 and 1941, the town’s male population rose from 600 to about 2,500. Juba’s population reached 4,135 by the end of the war and doubled, reaching 8,265 during the next four years (Mills 1981).

For Juba’s authorities, the cinema’s popularity among young people and all the new arrivals from rural areas focused broader anxieties about urbanization and change in the country. The Governor General’s Report for 1942-44 noted a worrying increase of petty theft in Juba, which the report attributed to the large number of laborers employed there, alongside increased traffic offenses and fatal accidents, attributable to military vehicles and the ‘drunkenness of the drivers.’[7]Governor General’s Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1942-44 (inclusive), p. 187 All this growth and excitement, together with the return of soldiers with their wages to a town which lacked much to spend it on, helped to encourage the growth of beer parlors, dance halls, gambling places, and other inexpensive pass-times, such as lodging appeals to court cases.[8]Owing to rationing and shortages. Governor-General of the Sudan. Report on the Administration, Finances and Conditions of the Sudan in 1945. Governor-General of the Sudan. Report on the … Continue reading Officials across the country worried that new residents would fall into crime and delinquency. Cinemas were commonly singled out for their ‘great influence upon in-migrants’ and ‘the youth,’ whom, one observer wrote, were thought to be ‘more susceptible to the effect of the Cinema, where they are stimulated to violence and crime by the highly coloured episodes which they see on the screen.’ (Hadi 1972:188, quoted in Kindersley 2016:68).[9]Lord Milvertoni, The Colonial Territories, HL Deb 06 July 1955 vol 193 cc497-500.

It is not hard to see how fears about children’s and rural arrivals’ susceptibility to ‘highly coloured episodes’ might ultimately be based in anxieties about the loss of colonial and patriarchal control and authority. Indeed, it was not only British officials who were concerned by the changes that film might bring. In 1945, for example, the Nahud Town Council, a body composed of prominent Sudanese residents, rejected the proposal of a Syrian merchant to establish a cinema in Nahud by a vote of 15 to 4. The council members worried that a cinema ‘would only lead the children to squander their own & their parents’ pennies and introduce an unsophisticated audience to a cheap & immoralising mode of life.’[10]TRH Owen, letter to his father, August 17, 1945 (SAD 414/15/97-98). In Juba, parents often refused to allow their children to visit the cinema, fearing that what was shown there would cause them to become thieves or criminals.[11]Florence Miettaux, Au Soudan du Sud, le cinéma de Juba a traversé l’histoire tumultueuse du jeune pays (Le Monde 21 July 2021).

For British authorities and many parents, then, more diffuse anxieties about Sudan’s future and the changes brought about by rapid post-war urban growth coalesced around the influence of films on supposedly unsophisticated viewers: children and recent migrants from rural parts of the country. But for many viewers in the rapidly changing and growing city, the stories and scenes presented in film offered ways to rethink relations with each other and to reimagine communities that were both larger and smaller than southern Sudan. For others, the places pictured in films provided a view of a possible future for Juba; “tall buildings, riding motorcycles,” one cinema-goer recalled: “and every person was wishing, ‘I hope one day it will be like that here.’” For young people, film provided material for creatively fashioning new kinds of adulthoods and reimagining their place in the world.

Audiences in Juba engaged with the films that were shown there, playing a role that made each performance different. Some cinema-goers were silent, gripped by the story or, sometimes, asleep; others booed or laughed or shouted at the screen, or provided running translation or commentary. People sometimes threw things. “Once a man brought a spear,” one cinema-goer told Juba in the Making’s co-founder, Florence Miettaux. “And when the action got too dangerous for the hero, he threw it on the screen to kill his enemy! Then the spears were banned in the cinema.”[12]I feel obliged to mention here the wide circulation of stories about cinema audiences mistaking what was being projected for reality. Most were probably untrue. But these stories were told again and … Continue reading It was thrilling. “At the start of the film, you would silently follow the action to understand what was going on,” another viewer told Miettaux; “and then, once you had started supporting a character, you couldn’t help yourself—you’d start shouting automatically: you were trying to warn him when another attacked him! »[18]Florence Miettaux, Au Soudan du Sud, le cinéma de Juba a traversé l’histoire tumultueuse du jeune pays (Le Monde, 21 July 2021)

What was playing?

Between March and July, 1960, the Juba Picture House exhibited more than forty different films in four languages.[13]This paragraph is drawn from notices placed the Equatoria Daily News Bulletin (JUB EP/36/F 1950-1960). By 1960, Sudan had the highest per capita cinema attendance in Africa south of the Sahara. There … Continue reading Several films were shown for several successive days. Most were in technicolor; some were black and white. Few films had been released more than three years prior to their exhibition in Juba. There were westerns, adventures, legal and crime dramas, spy thrillers, science fiction films, war films, romances, and wildlife pictures, from the United States, England, India, Egypt, and Russia. On Sunday, April 3rd, audiences were offered a costume drama set in ancient Egypt. On the following Monday, Rock Hudson thrilled the staff of the Information Office in Juba with his performance in Farewell to Arms (1957), a ‘marvellous picture in Cinemascope & colour.’ In May, audiences watched a flying saucer settle on a field in Washington DC in the Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), the Beat Generation (1959), Up Periscope (1959), a World War II movie about a submarine, and Chori Chori (1956), which begins on a yacht. Al-Wessada al-Khalia (The Empty Pillow, 1957), a film about a man getting over his first love played three times between April 6th and April 10th.

Hollywood films

Juba had been massively transformed by the war of 1939-45, but the cargo and vehicles moving through the town along the African Forces Line of Communication provided only a very limited window on the world that was at war. American war films gave a fuller picture—albeit one that was often upside down, or falsely colored, missing important elements, or otherwise distorted. These films were full of all sorts of propaganda and stereotypes, but they also pictured places that were very much on people’s minds. Juba’s audiences had long been perfectly aware that the understanding that they could gain through propaganda was partial and incomplete, taking it for granted such things had to be understood critically. And the films were a lot of fun.

The Cinematograph Ordinance of 1949 established a Cinematograph Board, which, during its first meeting in April of 1950, established a series of principles for application by censors based on the American Motion Picture Production Code. The Cinematograph Board limited the themes that were explicitly explored by films shown at the Juba Picture House. But, still, stories about adapting to postwar life in the United States echoed experiences in Juba in the 1950s. Hollywood films of this era often explored the contradictions between soldiering and family, the difficulties faced by returning American servicemen, and post-war anxieties. Changing relations between men and women supplied a popular theme. On Sunday, April 24, 1960, the Juba Picture House showed “She Devil” (1957), a misogynistic horror film about what happens when a woman is no longer afraid of male violence. In the film, a scientist develops a serum by distilling putrefied fruit flies which he administers in turn to a guinea pig, a cat with a broken spine, a rabid dog, a chimpanzee with “double pneumonia,” a lacerated leopard, and a woman with tuberculosis, Kyra Zelas (Mari Blanchard). The serum gives Kyra superpowers (she’s able to change her hair color, recover from any sort of injury), and she goes on a crime spree.

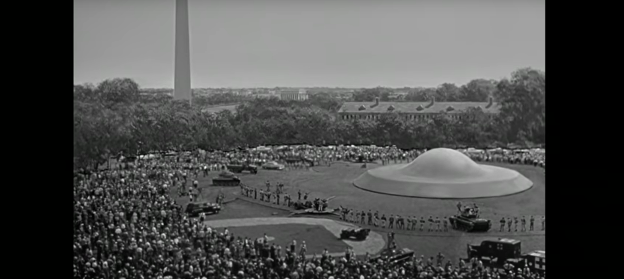

Another science fiction film, “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951), was shown at the Juba Picture House the following week on Tuesday, May 3, 1960. This film is about what happens when an alien from outer space named Klaatu, accompanied by a giant robot, Gort, lands a flying saucer in Washington, D.C., and issues a warning: “join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration.” The film’s producer, Julian Blaustein, said the film was meant to argue in favor of a “strong United Nations.”[14]Blaustein later produced Khartoum (1966), which starred Charlton Heston as Charles Gordon and Laurence Olivier as Muhammad Ahmed.

Westerns

The establishment of the Juba Picture House coincided with the ascent of the Western as a popular genre globally, which—together with the fact that many of the men we spoke to were born in the mid-1950s and first attended the cinema as boys—helps to account for the prominence of Cowboy films among those films mentioned by the cinema-goers that we spoke to. These films were also inexpensive for commercial cinema proprietors to obtain.

Westerns often seem to be fairly explicit meditations on the relations between masculinity, violence, and the imperial frontier. But it was the mix of hardscrabble effort and cowboy bravado that may explain their appeal to young people in a place like Juba, where many felt vulnerable being so far from home. The historian Ch. Didier Gondola describes in Tropical Cowboys (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016) how Hollywood westerns provided young people in the 1950s with material for reimagining masculinity in colonial Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), where colonial authorities infantilized Congolese men.

Most of the cinema-goers we spoke to were men, well-educated civil servants who had done much of their growing up in Juba. Many were in their late fifties. A few were older. The period of their recollection of the cinema ran from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Their personal narratives of cinema-going were often stories about growing up—stories about how, as boys, they had made bamboo swords for games inspired by Zorro, or played Cowboys (“No one wanted to be an Indian”) in schoolyards and scrublands.

“When we were still young boys, we liked cowboy films. If the film is a Cowboy, then we all rushed to it: because we want to see the star man shooting with the revolver. How to use the revolver was very impressive to us. We’d go to the school in the evening. And then everybody took a position. Then, if you saw him and he didn’t see you, you would make your fingers [into an L-shape] like this and point and say, ‘pa-PEWM! pa-PEWM!’ And that means you killed him with the pistol. When you shoot him, then he is out [of the game]. Or sometimes we do that in the bush. Because the grass will be so tall. Nobody can see the other one. We’d go and hide in the tall grass—and then we were in there shooting ourselves.”[15]Interview: 10 October 2017, Hai Cinema, Juba

Another man told us that he was introduced to the cinema by a friend of his who liked cowboy films and later joined the army. He described how, as he grew older, he would find some excuse to refuse his friend’s invitation to see a western. ‘Those cowboy films were all the same: a guy walks into a bar and starts fighting,’ he said. As he got older, he said, he came to prefer Indian romance films. Particularly, the musical numbers: the part where ‘a young man sings to a young lady who [feigns indifference] for a while—then sings to the man.’

Indian romance films

Brian Larkin (2003) has written about how for Hausa film-goers in Nigeria, Indian films provided a kind of ‘parallel modernity,’ that is, a look at the lives of people living in another newly-independent country, where people were reckoning with their own legacies of colonialism.

Many of these films explicitly probe questions about social change and ‘tradition,’ a domain customarily marked in film by marriage celebrations, food, village life, and song, and centered around concerns about who to marry and what language to speak. Like Egyptian films of the period, many concerned love marriages and the drama that followed young people’s efforts to navigate different ambitions, differences of wealth and poverty, and choices about love.

Films about how people redefined their relations with each other in the midst of profound change would have resonated in Juba during the years after the Second World War. In May 1960, for example, audiences at the Juba Picture House saw Chori Chori (1956), a Hindi-language remake of It Happened One Night (1934), which ran several nights at the theater. Chori Chori tells the story of what happens when a wealthy young socialite, Kammo, runs away from her father and meets a poor journalist who’s recently lost his job. Though the film begins on a luxury yacht anchored at British Ceylon, most of the film takes place in familiar places: on a crowded bus, along the roadside where women roast maize on braziers, beside a river, and on farm fields.

A handful of Juba’s Hindi-speaking residents may have been able to follow the film’s dialogue without the aid of Arabic subtitles. Some of Juba’s ex-soldiers may have visited the places represented in the film, having served in British Ceylon and India during the Second World War. Most audience members could enjoy the film and follow the plot (without the help of Arabic or English subtitles): an argument between a father and a daughter provokes a long journey, shown with buses and roads and sleeping in fields, punctuated by song-and-dance numbers, and concluding after some more peregrinations with romance.

Hai Cinema

Films made for wider audiences about Sudan have often been preoccupied with violent encounters between Sudanese and outsiders (Elsanhouri 2017). This theme runs like a bright red thread through Sudan’s and South Sudan’s appearances on the big screen: from the first film made in Sudan, John Bennet Stanford’s 1898 “Alarming Queen’s Company of Grenadier Guards at Omdurman,” which showed some infantry soldiers at Kerreri on the day before the battle at Omdurman standing up, fixing their bayonets, and marching away, through seven versions of The Four Feathers (made in 1915, 1921, 1929, 1939, 1955, 1978, 2002), Charlton Heston and Laurence Olivier’s confrontation in Khartoum (1966), and Machine Gun Preacher (2011).[16]On John Bennet Stanford see Stephen Bottomore, Filming, faking and propaganda: The origins of the war film, 1897-1902 (Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University, 2007). The historian Douglas Johnson … Continue reading It is no wonder that the filmmaker Simon Bingo, who helped to organized South Sudan’s first film festival, publicized the event by saying: « What we know now is that people are talking of South Sudanese as fighters, war people [who] like fighting, but we are struggling to try to change that. »[17]Conor Gaffey, The Juba Identity: South Sudan’s First Film Festival Recasts Its Image, Newsweek (7 July 2016). … Continue reading The films that have most appealed to South Sudanese audiences are not those about how imperial regimes have conquered and oppressed people but rather films about how, as a result, people in different times and places have ended up reconsidering their relations with each other.

Brendan Tuttle

References cited

Bottomore, Stephen. 2007. “Filming, faking and propaganda: The origins of the war film, 1897-1902.” PhD Diss., Utrecht University.

Duot, Joseph Chol. 2017. “A Research Report on Leisure Activities, Films, Fashions, and Popular culture in Hai Cinema, now Emmanuel Diocese, Juba (1962-2017).” Unpublished report.

Elsanhouri, Taghreed. 2017. “Backstage with ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy,’ Reflections On the Representational Influences on Filming Our Beloved Sudan (2011).” In African Film Cultures: Contexts of Creation and Circulation, edited by Winston Mano, Barbara Knorpp, Añuli Agina. Cambridge Scholars.

Fortescue, John. 1912. Narrative of the Visit to India. London: MacMillan and Co.

Hadi, Abdullahi Mohammed Abdel. 1972. “The Impact of Urbanization on Crime and Delinquency.” In Urbanization in the Sudan, edited by El-Sayed Bushra. Khartoum.

Ibrahim, Kamal Mohamed. 1999. “A Brief on Cinema in Sudan.” Sudanow (April 1999): 38.

Kindersley, Nicki. 2016. “The fifth column? An intellectual history of Southern Sudanese communities in Khartoum, 1969-2005.” PhD Diss., Durham University.

Larkin, Brian. 2003. “Itineraries of Indian Cinema: African Videos, Bollywood, and Global Media.” In Multiculturalism, Postcoloniality, and Transnational Media, edited by Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, 170-92. Rutgers University Press.

Lwoki, Sayed Benjamin and M.R. Morgan. 2005[1954]. “Minutes of the 1954 Liberal Party conference in Juba (October 18th-21st, 1954).” In The Southern Sudanese Pursuits of Self-Determination: Documents in Political History, edited by Yosa H. Wawa. Kampala: Marianum Press.

Mills, L.R. 1981. The People of Juba: Demographics and Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Capital of Southern Sudan. Juba: University of Juba.

Seri-Hersch, Iris. 2011. “Towards Social Progress and Post-Imperial Modernity ? Colonial Politics of Literacy in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1946-1956”, History of Education 40(3): 333-356.

Sikainga, Ahmad Alawad. 2015. “Sudanese Popular Response to World War II.” In Africa and World War II, edited by Judith A. Byfield, Carolyn A. Brown, Timothy Parsons, and Ahmad Alawad Sikainga, 462-479. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swanzy, H. 1947. “Quarterly Notes.” African Affairs 46, no. 183: 71.

Symes, Stewart. 1946. Tour of Duty. London: Collins.

Yangu, Alexis Mbali. 1966. The Nile Turns Red. New York: Pageant Press.

References

| ↑1 | Lord Kitchener, Consul-General in Egypt at the time, had come to Sudan to greet the King and Queen. |

| ↑2 | Governor-General of the Sudan. “Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1942-44 (inclusive).” 126. |

| ↑3 | Governor-General of the Sudan. “Report on the Administration, Finances and Conditions of the Sudan in 1947.” 144. For a comparison of numbers reached by mass literacy campaigns, see Seri-Hersch (2011). For standard equipment and budgets from mobile film units see L.N.M Newell to Governor, UNP, “Mobile Cinema,” 25 November 1951. JUB UNP/92/B/1 – 43. During the first years of the travelling cinema, commentary was provided by Inspectors or senior teachers ‘knowing the local language who hear the English commentary through once or twice first.’ During later years officials sometimes accompanied mobile cinemas ‘so that the operator and driver will not be tempted to use the van for their own ends.’ P. Le Fleming. “Southern Provinces – Mobile Cinema,” 20th June 1952. JUB EP/108/B/2 – 76-7. [1] US Department of Commerce, 1944. “Sudan Railway’s ‘Public Enlightenment’ Car.” Foreign Commerce Weekly 14, no. 1 (January 1, 1944), 24. |

| ↑4 | US Department of Commerce, 1944. “Sudan Railway’s ‘Public Enlightenment’ Car.” Foreign Commerce Weekly 14, no. 1 (January 1, 1944), 24. |

| ↑5 | Public Relations Office, Catalogue of 16mm. Films (February 1952). |

| ↑6 | One person that we spoke to said the car was a Peugeot. |

| ↑7 | Governor General’s Report on the Administration of the Sudan for the years 1942-44 (inclusive), p. 187 |

| ↑8 | Owing to rationing and shortages. Governor-General of the Sudan. Report on the Administration, Finances and Conditions of the Sudan in 1945. Governor-General of the Sudan. Report on the Administration, Finances and Conditions of the Sudan in 1945, p. 197 |

| ↑9 | Lord Milvertoni, The Colonial Territories, HL Deb 06 July 1955 vol 193 cc497-500. |

| ↑10 | TRH Owen, letter to his father, August 17, 1945 (SAD 414/15/97-98). |

| ↑11 | Florence Miettaux, Au Soudan du Sud, le cinéma de Juba a traversé l’histoire tumultueuse du jeune pays (Le Monde 21 July 2021). |

| ↑12 | I feel obliged to mention here the wide circulation of stories about cinema audiences mistaking what was being projected for reality. Most were probably untrue. But these stories were told again and again partly because they captured the feeling of being gripped and enthralled by film and, partly, because they reflected metropolitan prejudices about rural and “unsophisticated” audiences. Gadallah Gubara, a cinematographer who worked on Sudan’s first mobile filmmaking unit, tells a similar story in his memoir, Hayati wa al-sinima (My life and Cinema, 2008). For a critical discussion of such ‘first contact’ narratives and their politics see: Stephanie Newell. 2017. “The Last Laugh: African Audience Responses to Colonial Health Propaganda Films.” The Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry 4, no. 3: 347-361. Timothy Burke. 2002. “‘Our Mosquitoes Are Not So Big’: Images and Modernity in Zimbabwe.” In Images & Empire: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa, edited by Paul S. Landau and Deborah D. Kaspin, 41-55. University of California Press. James Burns. 2000. “Watching Africans Watch Films: Theories of spectatorship in British Colonial Africa.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 20, no. 2: 197-211. |

| ↑13 | This paragraph is drawn from notices placed the Equatoria Daily News Bulletin (JUB EP/36/F 1950-1960). By 1960, Sudan had the highest per capita cinema attendance in Africa south of the Sahara. There were 34 purpose-built cinemas in the country with a combined seating capacity of 60,000. Arno George Huth, Communications Media in Tropical Africa: Report Prepared for the International Cooperation Administration (International Cooperation Administration, 1961), 50-51 |

| ↑14 | Blaustein later produced Khartoum (1966), which starred Charlton Heston as Charles Gordon and Laurence Olivier as Muhammad Ahmed. |

| ↑15 | Interview: 10 October 2017, Hai Cinema, Juba |

| ↑16 | On John Bennet Stanford see Stephen Bottomore, Filming, faking and propaganda: The origins of the war film, 1897-1902 (Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University, 2007). The historian Douglas Johnson has pointed out that for many filmmakers, Sudan and South Sudan provide a stage upon which “to portray an essentially European moral struggle, beset by doubt, but redeemed by sacrifice.” Douglas H. Johnson, “Why The Four Feathers? (why not seven?),” Sudan Studies 34 (2006), 14-19. |

| ↑17 | Conor Gaffey, The Juba Identity: South Sudan’s First Film Festival Recasts Its Image, Newsweek (7 July 2016). https://www.newsweek.com/juba-identity-south-sudans-first-film-festival-offers-new-image-war-torn-478131 |

| ↑18 | Florence Miettaux, Au Soudan du Sud, le cinéma de Juba a traversé l’histoire tumultueuse du jeune pays (Le Monde, 21 July 2021) |

Hai cinema,

Hai Malakal

Hai Neem

Nyakuron cultural centre

To Station